Huyfárah

| Huyfárah lu-serin æm Huyfárah | |

| |

| Capital | Ussor |

| Major cities | Miədu Mæmedéi Sertek |

| Languages | Fáralo |

| Demonym | Fáralo |

| Government | monarchy |

| Formation | c. -400 YP |

| Collapse | c. 800 YP |

| Successor states | Wippwâ Mɨdu etc. |

| Credits | |

| Created by | Zompist |

| Edit me | |

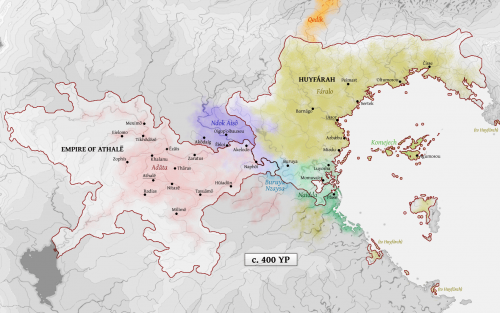

Huyfárah (Faraghin: Soifaragh, "Faraghin coast") is a nation of Akana, located north of the Eigə delta. It was one of the most powerful states in the 1st millennium YP, setting up a maritime empire and founding colonies all along the coast between Xšalad and Siixtaguna.

History

Timeline

- c. -1400: Faraghin conquer Oltu valley.

- -1310: Faraghin break into multiple baronies.

- -1258: Temporary Ndak reconquest of lower Aiwa and Oltu valleys.

- -1170: Faraghin regain control of the Oltu.

- c. -800: Truce of Deunagho between Faraghin barons enables burgeoning trade and settlement.

- -762: Sertek founded by Fáralo merchants, establishes itself against Feråjin on the Poráš.

- c. -650: Wars with Sertek end the Truce of Deunagho; many Fáralo settle away from the fighting as far as Kasca and Oltumosou.

- -520: Barons of Ussor conquer Miədu.

- -480: Ussor invades Kasca, and quickly conquers the delta till Påwe and Momuva'e push it back; decades of war follow, ending with Ussor controlling half the delta with nominal control over the rest. Miədu drifts in and out of Fáralo control.

- c. -400: Fáralo naval expedition discovers Siixtaguna, bringing back several Etúgəist monks.

- -198: Mentek, baron of Ussor, unites Huyfárah, beginning the Balanin dynasty.

- -185: Huyfárah occupies the Dagæm islands, beginning its imperial period.

- -167: Huyfárah in control of Oltumosou; begins pacifying the inland Feråjin.

- -142: Čisse founded in order to protect Huyfárah's eastern border against the Doroh.

- -133: Miədu, seeing which way the wind is blowing, voluntarily joins to Huyfárah.

- -112: Påwe conquers Momuva'e, leading to war with Huyfárah.

- -109: Huyfárah conquers Momuva'e (though it does not hold it for long) and occupies most of the Kascan delta.

- late 220s: Balanin civil war in Huyfárah; Fáralo Golden Age ends.

- 230: Ascension of Etou I; under his rule Huyfárah expands west to the borders of Lašumu.

- 248: Etou I dies; ascension of Etou II.

- 255: Failed Fáralo invasion of Lašumu: Supply lines of Etou II are cut by Athalēran military.

- 294: Etou II dies; civil war in Huyfárah.

- 295: Gadein I emerges victorious and becomes emperor.

- 312: Gadein I dies; ascension of Etou III.

- 318-319: Military campaign of Etou III against the Talo and Puoni.

- 319: Exodus of the Puoni.

- 326: Etou III dies; ascension of Gadein II.

- 328: Various Kascan towns become vassal states of Huyfárah by treaty

- Mid-300's: The port town of Azbǽbu grows to great size.

- 343: Gadein II dies; Baodan I starts the Maléi dynasty.

- c. 343-405: Fáralo Silver Age.

- 351: Acquisition of Buruya.

- 363: Huyfárah absorbs more of Kasca, including (de jure anyway) Momuva'e.

- 370: Huyfárah claims rule over Fmana-hŋ-Talam. A planned city is begun.

- 375: Baodan I dies; ascension of Ŋamíga I.

- 405–443: Declining stability: Several natural disasters hit; barbarian raids; power shifts toward Sertek as emperors relocate there (but the official capital, and the Senate, remains in Ussor).

- 444–453: War between Huyfárah and Athalē, resulting in Fáralo control over Lašumu.

- 453–489: Recovery; Lašumu is organized as a client state of Huyfárah.

- 489–546: The decline begins: Lašumu is lost again and the southern half ceded back to Athalē; the treaty states that northern half will remain independent as long as it is not dominated by Huyfárah in any way. Meanwhile Athalē encroaches along the Eigə. The emperor is removed by the Senate for having lost the war, but returns two years later after his replacement is assassinated. A sense of unease and moral decay. More assassinations. Buruya is lost. The natives of Fmana-hŋ-Talam push back the Fáralo to the north end of the island.

- 547–584: Gigantic, confused, multi-phase civil war, among three principal factions. In the aftermath, the Maléi Dynasty is deposed, the empire shrinks further, and loses the coast from Mæmedéi south, which reorganizes as Lewsfárah ("Free Fárah"), a federation of city-states run by religious and political reformists (calling themselves the Zgeiru, "Atheists").

- 579–584: Lewsfárah stops fighting Huyfárah, but it is mired in revolutionary chaos.

- 600's: Takuña pirates establish small footholds in areas of ineffectual rule within the disintegrating empire; Čisse secedes as an independent city-state.

- 786: The bitter end of the empire comes with the sack of Ussor by a faction of the Doroh.

- late 700's: Lewsfárah is dissolved, and splits into its constituent city-states. Mɨdu and Azbǽbu vie for naval dominance.

- 786-800's: Isthmus chieftains rule over the Oltu Valley. Gradually they are linguistically absorbed by Fáralo-speakers.

- mid-800's: Fáralo landowners depose the Doroh rulers, and proclaim a kingdom of Woldulaš, consisting mostly of the Oltu Valley.

Settlement of the North Coast

In ancient times, the Oltu river valley and the nearby seacoast were divided between two related peoples, the barbaric Faraghin and Feråjin. The civilized world was to the south, along the great Eigə river. The first civilized people were the Ŋouru, who arose in the river delta - Kazəgad - about 4000 years before classical times. The peoples and wars of the valley were many, but for our purposes the chief fact was the conquest of Kazəgad by the Edák, a people who had lived upriver, in Lašumu.

The Edák were themselves conquered more than once, but their edge in population allowed them, each time, to expel or absorb their conquerors. They emerged from the last of these episodes with a new imperial vigor, and set themselves the task of conquering the known world. They reached their greatest extent around -1900 YP under the emperor Siənčæn: the entire Eigə valley, the southwestern mountains once held by their rivals the Gezoro, a wide stretch of the eastern seacoast, and the lands of the Feraghin and Feråjin.

This latter region they called Hagíbəl (Ndak Ta: Sau Ibli), the North Coast; they colonized the seacoast and river valleys, leaving the Faraghin (and to a lesser extent the Feråjin) to the mountains, forests, and pasturelands. For some centuries the Edák remained as overlords; then they lost the hinterlands; then the empire collapsed, leaving the local Edák ruling the colonized areas. The local balance of power reversed: the Faraghin hill tribes, accustomed to horses and frequent internecine war, raided the Edák and pillaged or even razed their main settlements.

The Faraghin conquest

Around -1400 YP, the Faraghin put aside their usual disunity and conquered the Oltu valley and its capital, Ussor, and then the Edák littoral, which they renamed Huyfárah, the Faraghin Coast. This time, the horsemen were here to stay. Edák society - highly stratified and urbanized - was transformed. As nomads, the Faraghin believed not in real estate and civil protection but in moveable property and honor. For the settled Edák, the archetypical villainy was murder; for the Faraghin it was theft. (Murder could be paid for.)

If this seems barbaric, we should recognize as well that the Faraghin were much more individualistic and enterprising than the Edák, whose devotion to stability led less to peace than to stagnation. It was possible to move up in Faraghin society, and trade and markets developed here, while the Eigə valley was still dominated by archaic command economies.

The great vice of the Faraghin warrior class was a disinclination, on the death of a respected king, to support their unproven young heirs. The unity of the Oltu lasted only a century; the region then became a squabbling patchwork of baronies; if some ambitious ruler unified them his kingdom would collapse in a few generations. Once the littoral was even temporarily reconquered by a resurgent Kazəgad.

Nonetheless, trade continued to flourish, and the people of Huyfárah developed a great skill in navigation, and explored the littoral a great distance to the east and south.

The Golden Age of Huyfárah

The turning point was the discovery of the nation of Histuənə (Siixtaguna), to the east, and its religion Etúgə. Its great sage Hutaba preached nubázi "the realization" - the realization being that all knowledge is false; only action (etúgə) and belief (mušitugə) are real. Nubázi frees the spirit to live in ifisænə, the spiritual world.

The explorers brought back Etúgəist monks. These were at first mocked, even persecuted and tortured; but their calm conviction and eloquence won respect. Finally the entire country was won over, and the new doctrine not only consolidated Fáralo identity, but brought a new respect for unity and loyalty. The Balanin dynasty, able generals and devout Etúgəists, unified the country, and soon turned to empire-building. First the Dagæm islands were occupied - a useful acquisition for a maritime empire; then the lands of the Feråjin just to the east, then Kazəgad - which was by now, however, only a poor shadow of its former glory.

The people of classical Huyfárah called themselves the Fáralo - essentially a form of "Faraghin" - and thought of themselves as descendents of this warrior nation. Nonetheless their language descended from that of the Edák (that is, Ndak Ta), though with heavy Faraghin influence.

The Etou dynasty

In 226 YP, the last Balanin emperor of Huyfárah died without issue at an early age. He had had no close relatives beyond his wife, so a search was conducted to determine his most closely related cousin who could then assume the throne of Huyfárah. The search produced multiple candidates who were all equally closely related; two of these proclaimed themselves emperor, and the resulting conflict boiled over into civil war: bloody, but mercifully short. When it was over, no living Balanins remained.

The former emperor's wife, while not a legal candidate for the throne, was power-hungry and politically skilled. She succeeded in manipulating the nobility and Senate into accepting her lover - a powerful noble in his own right - as the new emperor of Huyfárah, and he was crowned with little more drama than the muffled muttering of the discontent.

Unlike the Balanins, the new emperor Etou I was not a devout Etúgəist. He made lip service to the religion, but did not personally uphold its tenets. Overall he was not a bad ruler, however, and under his reign the Empire healed from the civil war and began to expand its borders once again - this time succeeding in bringing the entire western forest region and its inhabitants, the Tlaliolz, fully into the Empire.

However, his son Etou II was nowhere near the competent leader his father and the Balanins were: instead of inspiring his people, he manipulated the institutions and machinery of Etúgə for personal gain. Using Etúgə as a banner to inflame his armies with fervor to conquer the infidels, Etou II blundered into Lašumu, tried to assimilate the entire region at once, and watched the invasion blow up in his face when his insufficiently defended supply lines were cut. Hiding this disaster from the citizens at home, he took his armies north to harass the Tlaliolz - a people he already nominally controlled - because they remained non-Etúgəist and thus out of his full control.

This was the action that finally went too far. When word reached Ussor, those citizens who had already had enough of the corruption of Etúgə took matters into their own hands, rioting and burning the Imperial Palace and its associated temple of Etúgə. The temple, after all, was only stone and mortar; the truth of Etúgə was eternal with or without a building. The uprising was not to last, however. Etou II and his armies returned home angry as a wasp and put the nascent rebellion down like a rabid dog. His regime remained entrenched for another four decades while discontent simmered and the machinery of Etúgə was exploited to keep his citizens in check.

During this time, nominal membership in Etúgə rose while devout belief became rare. Many people were bitter: the older generation for the perversion of what to them had been the one, true, and serious religion, and the younger generation in resentment for being ruled by fear. It was in these fertile grounds that the seeds of further revolt were planted. A number of young thinkers rose to covert influence by preaching against Etúgə's use as an instrument of control. Many of these were discovered and arrested, while the smarter ones kept meetings quiet. But their actions over the last decade of Etou II's rule brought about a segment of the population in the central cities that had renounced Etúgə and wanted a change. The most faithful of these prepared and waited for the day action could finally be taken.

In his nineties, still iron-fisted and authoritarian as ever, Etou II finally died by tripping one morning over his own robes and cracking his head by sheer accident. It did not take long for word of the emperor's demise to spread; one of his own grandsons was secretly among those who preached against Etúgə. Within 24 hours Ussor was in riot. Within the week, so were all the other cities of the central Empire.

Both of Etou II's sons had already passed on by the time he did; he left only grandchildren. Two of these became important: Gadein, the heir apparent, ascended to the throne early the next morning while his city was aflame, and Daodas, the aforementioned anti-Etúgəist, rose to ascendancy among the rebel forces over the next several days.

Gadein proved quickly to be a true heir, being just as corrupt as his grandfather. But it took him a little too long to gather and reorganize the army to his side, time in which the growing rebellion continued to organize out of the early chaos and gather steam. In the end, however, Gadein did prevail. It took months, but he succeeded in driving the rebel forces out, first from Ussor, and finally from the other nearby cities. What was left, a rather ragtag army of perhaps a hundred thousand, saw how the wind was blowing, and Daodas convinced them to flee west to the hinterland province of Tal.

Calling themselves the Epuonim (modern term Puoni), "infidels", Daodas' people took up residence with the Tlaliolz (modern term Talo) - who still had yet to embrace Etúgə. There can be no doubt that this was not a coincidence.

The exodus of the Puoni

A generation passed. The two groups - Talo and Puoni - intermarried and became as one people. Gadein died, leaving the throne to his son Etou III. This fourth emperor of the Etou Dynasty was finally a ruler competent enough to lead Huyfárah well. He made peace with many of his father's enemies, and concentrated a much larger portion of the imperial funds on improving agriculture and rebuilding the navy. He also restored the long-burned temple of Etúgə and encouraged the remaining true believers of the faith - the now rare breed descended in spirit from the original sincere Etúgəist population - to come forth and proselytize. In time, the religion healed and gained converts once again by merit instead of by threat. But nobody is perfect. Etou III also inherited his father's few passionate hatreds largely intact, first and foremost his hatred of the Puoni and Talo for their continued stubborn disinclination to be good citizens. After a decade of careful nurture of the Empire, Etou III once again roused the Imperial regiments to go west and do something about the infidels in their lands once and for all.

Very much a Balanin in spirit if not in name, Etou III proved to be as capable a general as he was a ruler. To make a long story short, he made quick work of many of the inhabitants of the west, routed many of the survivors out of the forests, and made quick work of them too. Nearly half a million were marched back to Ussor in chains, and later distributed throughout the Empire as indentured servants, who eventually became known as the Toło ethnic group. A sizeable portion of these were sold to foreign lands as slaves.

Only a remnant of the westerners were left - perhaps two hundred thousand. Since the forests along the border had finally proved insufficient to secure them from too much Imperial control, and with the other 2/3 of their population deported, the remainder fled south. The army pursued them and exacted heavy casualties from them, but the majority made it to safety across the Eigə river. Wanting to put more distance between them and Ussor, they continued south into the forests of Kuaguatia, at the inland southern fringes of Kasca. Now calling themselves only Puoni, they settled in those lands and have been there ever since. Daodas is said to have lived just long enough to see his people firmly settled in their new lands in his dotage, finally dying that same year, after having guided them well for three decades.

The Silver Age

Etou III's heir Gadein II did not share his father's hatred of the Epuonim. Those who had been sold as indentured servants retained their religious beliefs, and within a generation - by the middle of the 4th century - many were able to buy their emancipation from their masters. Once free, they formed close-knit communities in the major Fáralo cities such as Miədu and Ussor.

During this time, Huyfárah grew more powerful by absorbing much of Kasca as client states in 328. Gadein II died peacefully in 343. He had no male children, and there was a brief dispute for the crown before a cousin by marriage, Baodan of the House of Maléi, was named. The Maléi were based in the Poráš Valley, near Sertek; they were the first noble family of Feråjin descent to rule the nation (at this point the ancient tribal distinction was merely ceremonial).

Baodan I was by all means one of the greatest emperors of Huyfárah. He had a keen understanding of economic policy, and devoted his reign to the purification and promotion of Etúgə - the Temple was given heightened powers - keeping the people well-fed, and conquering lands afar. He also built up something of a cult of personality, with statues of him adorning many public places, such that a diminutive form of his name later came to actually mean "statue" in some dialects.

His policies, coinciding with the acquisition of Buruya as another client state in 351, were contributing to a strong economic boom during this period. This, with ensuing cultural developments, led to what is known as the Fáralo Silver Age, roughly encompassing the second half of the fourth century YP and perhaps continuing into the fifth. It was so called because the Golden Age was looked back to as a time of perfect, strict morality and social harmony; the Silver Age empire far surpassed it in wealth and power, but its multicultural atmosphere was frequently attacked as "decadent", and certain societal fissures were emerging that caused an atmosphere of increasing uneasiness. (The usage of "Gold" and "Silver" here is merely a translation into familiar Western terminology. The Fáralo terms were in fact the "Red Age" and the "Little Red Age.")

At the dawn of the fifth century Huyfárah, under the reign of Lewspran II, was at its territorial and perhaps cultural zenith. It commanded outposts from Lasomo to the jungles of the Mrisaŋfa peninsula to the rocky islands of Sumarušuxi. New and strange religious cults were imported and intermingled, though nearly all under the umbrella of loyalty to the great Temple of Etúgə in Ussor - the largest social organization of its era.

The Temple was conceived as the apex of a great pyramid governing the social and moral structure of society. Likewise the Imperial Court was situated at the top of its own pyramid, representing the state's power to protect and feed its citizens. But these two seemingly omnipotent and parallel forces were in fact countered by two powerful classes - one of ancient lineage, the other only nascent.

The first were the aristocratic landowners - conservative, locally-minded, wealthy but rustic, priding themselves on pure Faraghin (occasionally Feråjin) descent, at least on the male line. Once they had ruled the nation, but now in effect represented only a portion of it - the Home Provinces north of Ussor. The aristocrats were found elsewhere (the South, the East, Kazəgad, Dagæm), but only as local toeholds of the families from the homeland. There they commanded large estates, raised beautiful horses, and intermingled as little as possible with the locals, especially in Kazəgad.

Each noble family sent a representative to the Senate in Ussor, whose power was only advisory, except in the matter of resolving dynastic disputes and confirming the new emperor.

The second, nascent class was the rising bourgeoisie in the cities (pei lu-zmeibu, the "Big Traders"), especially in the South, who largely controlled luxury trades and financial services. They were typically loyal to the emperor, only ambivalently loyal to the Temple, and contemptuous of the lords. They were noted for frequently taking a faddish interest in the various foreign cults.

Of final note, the most impressive technological development of this era was the construction of bigger and sturdier sailing ships. The coastal town of Azbǽbu, located at the northern edge of Suš Tæm Province, had a deep harbor that could accommodate these deeper-keeled vessels. It flourished as a major port, quadrupling in size during the fourth century, and becoming one of the major cities of the Empire. Its people were said to be fast-talking, hyperactive, and friendly but unscrupulous.

The Fifth Century

Various unrelated developments must be discussed here, all of which are cited as contributors to the later decline of the Empire.

A disastrous hurricane struck Kazəgad in 405, causing widespread destruction and rerouting several river channels. It became apparent that the Fáralo administrators had no understanding of the land and exercised little real control over the locals, especially as open rebellion began in the aftermath of the disaster, spearheaded by a bizarre, nihilistic cult known as the "Insects". The army was called in to put down the rebellion and became stationed there indefinitely. The situation was increasingly felt as a quagmire - the Imperial coffers were being "drowned in the mud".

The Kennan, an audacious and apparently fearless people from the east, ushered in a new Age of Piracy, disrupting trade routes and even mounting direct attacks on several Fáralo colonial outposts.

Lewspran relocated his court to Sertek during the summer, presumably to keep an eye on his cousins. When he died, one branch of these made a claim for the throne, but Lewspran's son Baodan III was ultimately upheld. Baodan and the later Maléi were ineffective and fairly uninteresting rulers, said to be controlled by their wives and advisors. The court moved to Sertek full-time.

Finally, beyond the empire's borders, in Oigop'oibauxeu, there lived a political philosopher named Mak'ed ge-Hoi (F. Maké), a member of the growing Etúgə presence among the Ndok. In an age dominated by two massive empires, with his city sitting uneasily in between the two, he envisioned a new kind of political structure, marrying the ancient republican customs of the Dāiadak with the ethical philosophy of Etúgə. In his imagined realm, power derives from the wealth of cities - the ideal being a patchwork of strong, individualistic city-states. It is a world of serenity, prosperity, and great religious devotion.

The end of the Silver Age is variously pinpointed at 405 (with the hurricane), 411 (the death of Lewspran II) or 444 (war with Athalē).

The Athalēran Wars

The southern half of Lasomo was ruled by Athalē, and by now largely spoke Adāta. Most of the northern half, excluding some fringe territories under Huyfárah, was controlled by several Ndok kingdoms. Previously these had been unified under the dominion of the great city of Oigop'oibauxeu, though in the past half-century its power had waned and the various city states had each gone their own way.

Emperor Mennat I took note of this fragmentary situation and invaded in the spring of 444, taking Oigop'oibauxeu by midsummer. The rest of the year was spent subduing the smaller neighboring kingdoms, and soon the region was essentially secure. Initially a repeat was feared of Etou's blunder, two centuries prior - but the natives remained fairly docile. Their attitude was one of bitter relief that Athalē, whose rule would surely be twice as disruptive and overbearing, had not invaded instead.

The smoke of the Fáralo campfires could be seen from Akelodo; Athalē inevitably sent its own force to counterattack. The fighting was fierce; what had been a fairly casual foray now became the focus of a national war effort. The frontier shifted back and forth several times, but nearly a decade later, with perhaps half a million dead and several cities burned, Akelodo capitulated.

Lasomo was reorganized as a client state; the Fáralo strategy was to subjugate the Adāta-speaking southerners to the Ndok-speaking northerners, while promulgating, in a rather two-faced way, a new spirit of national unity. A northerner, married to Mennat's sister, was crowned as king of Akelodo.

The spirit in Ussor was euphoric - the government in the following decades set to work repairing roads, building new ships and temples, and holding great religious ceremonies. The nobles toasted each other with the endless supply of Lasomoran sweet wine.

Athalēran power could be kept at bay as long as their former subjects were pacified, but it was a losing strategy. Akelodo rebelled in 489 and Athalē came to its aid. The king was publicly executed. In a mirror-image of the previous war, the Athalēran armies crossed the Eigə to the northern side and laid siege to Oigop'oibauxeu. A Fáralo army came to relieve the city but were beaten back deep into their own territory.

The Athalērans took Buruya in 494, and were advancing ominously towards Miədu when Huyfárah finally surrendered. Athalē held onto Buruya, and reasserted control over southern Lasomo; the northern half was allowed to remain free with Athalē's protection, once more acting as a buffer state.

The Ndok were in a nationalistic mood, and seeing as they were largely free to do as they wished, reorganized their state as a league of republics under the now wildly popular principles of Maké, who was being elevated as a national saint.

The Senate in Ussor cited an ancient right, unused in centuries, to remove emperor Mennat II, in 496. His replacement, Kečemin of Barnágo, was ultimately descended from the Balanin line; the notion was to make a clean start by symbolically going back to the beginning. The imperial court was moved back to Ussor; Mennat remained under house arrest in Sertek.

Kečemin spent two years rooting out pro-Maléi partisans, then was assassinated by a bodyguard. Mennat was reinstated, but himself was assassinated in 503. He had no children; the crown went to his nephew Jorin.

Political Crisis

The empire was still extremely powerful and influential and enjoyed a state of relative prosperity, but the national pride had been severely injured, and the chief problem now was a growing internal division between supporters of the Houses of Maléi and Kečemin. This translated essentially into a conflict between the populous Ussor Valley and the sparser but vast eastern provinces. The conflict was carried out mostly through terrorism and assassination, and the government was felt to be in an alarmingly weak and unstable position. Several outlying areas were subject to pirate raids of increasing intensity, some by the Kennan, who were terrorizing the Eastern nations, some by groups of Doroh and Sošunami. The navy was called in to repel a massive Kennan invasion of Dagæm in 533.

The southerners generally took neither side in the succession dispute, which had taken the lives of various government officials. Increasingly their anger was turned toward Imperial rule itself, though due to fear of overbearing reprisals against them, and also perhaps in emulation of Maké's restrained style, they tended to phrase their dissent in fairly gentle, metaphorical language. For Maké had recently been translated into Fáralo, and was a growing success among the Big Traders, especially now that their neighbor, Lasomo, seemed to be flourishing under his proposed political framework.

Nobody called for revolution explicitly, but merely for the integration of republican elements into the existing system. The running joke was that everyone had started speaking Adāta; you couldn't walk down the street without hearing people talking about alégadu, halenadu, satar. The Makéists first were derided as the flavor of the month; then, as they seemed to be growing in influence, the government issued propaganda condemning them as zgeiru, "atheists." The name stuck around as an epithet, then as an ironic badge of pride used by the Makéists themselves, finally being taken as the basic name for the movement.

Meanwhile, the Big Traders worked with the municipal governments in the southern cities to improve fortifications for defense against "partisans and vagabonds".

Buruya, too, was under the grip of Maké. It re-established itself as a city-state after a largely bloodless rebellion against Athalē in 519.

The partisan crisis came to a head when Mennat IV was killed in 545. The House of Kečemin had gained the approval of the Senate once again; 20-year-old Kečemin II became the new emperor. He took - in his adolescent way - a hardline stance: In 547 armed thugs were sent out in a general pogrom against the Zgeiru and pro-Maléi partisans, as well as, for good measure, the Toło. Hundreds were killed; residential areas in Ussor, Mæmedéi and Sertek burned for a week. Privately funded militias began springing up in the southern cities, and Zgeiru rhetoric now took on an explicitly revolutionary tone, calling for rule by elected officials, and in some cases, the removal of the Temple hierarchy.

The Civil War

Kečemin dispatched the army to force the cities to disband the militias. The troops, once inside the walls, were subject to covert terrorist attacks; the local officials feigned ignorance and blamed pro-Maléi partisans.

Meanwhile, the real partisans, funded by local aristocracy, rebelled in the east; a coalition of noblemen issued a declaration of their support for the Maléi pretender, Mennat V. The armies were largely withdrawn from the south to go deal with the bigger problem in the north.

The first major battle was fought in the early summer of 547, at the town of Derač in Sætlaš province. At first it looked like an easy victory for Kečemin's forces, as they advanced eastward, and his navy occupied Sertek and Oltumosou (Čisse Province supported him also, and remained largely outside the conflict). Kečemin himself served as a general at the front lines, and was killed in 550. His brother Jorinago was too young to rule, so the administration was effectively handled by their mother Deušan.

During this transition the Kečemins faltered, and some local armies switched allegiances: In 551 the pro-Mennat forces took Barnágo, then began a slow, bloody advance down the river to Ussor for the next two years. When it was clear the city would fall, the Imperial Court fled to Agumosou, with much of the Navy following.

The Zgeiru, meanwhile, were firmly in control of Miədu and Azbǽbu. Mæmedéi was ruled by a Kečemin faction; the revolutionaries made a provisional alliance with Mennat, and took the city. Then, in the winter of 553 the combined armies entered Ussor. Mennat was named as emperor by a reduced Senate consisting of only his supporters; he maintained a tenuous grip on the entire mainland except Čisse Province.

Now the war entered a strange latent phase while Mennat attempted to root out rebellion, but allowed the South to operate de facto independently. Deušan sat in her island paradise plotting revenge, building an impressive network of spies and assassins on the mainland. Mennat, uneasy, moved the court and even the Senate back to Sertek.

Peace on the mainland was shaky. Several new pretenders to the throne emerged, gathering local support in their territories and causing considerable havoc. A new, apocalyptic cult emerged among the southern revolutionaries, who advocated the violent destruction of all existing political systems. But the balance of power lay with the wealthy, Etúgəist core of the Zgeiru, which was in the process of consolidating control over local governments.

Secession

The revolutionaries were wildly optimistic at this point, still hoping that they could conquer Ussor and institute republican rule over the entire country. The strategy, for now, was to play the two imperial factions against each other. They drew up a constitution for a "free Huyfárah" in 558, but sent aid when pro-Kečemin elements revolted in the Oltu Valley. The alliance with Mennat was dissolved.

The new constitution appeased the Southern nobles by giving them ministerial positions and seats in the new Senate. Many also served as commanders of the Southern armies, a decisive factor as now they began to engage Mennat's forces directly.

Mennat spent the next year fighting the revolutionaries for control of Ussor. Deušan sent in the Navy, along with Sošunami mercenaries. Ussor was retaken, and Jorinago, now come of age, returned as emperor in 563.

He attempted to appease the revolutionaries, while executing thousands to liquidate any support for Mennat; most of the high-ranking clergy, who had been ruling the city, were put to the sword as traitors. This endeared the emperor to the merchant classes, especially in Ussor, some of whom repudiated the Zgeiru. Naval and land trade partially resumed in the region.

From mid-563 the rest of the second phase of the war was spent in a slow, bloody and monotonous advance by Jorinago against Mennat across the countryside. Mennat had very few naval forces, and relied on Doroh mercenaries to counter Jorinago's ships, but these tended to act more like pirates then soldiers, and could be easily co-opted.

Meanwhile it had become clear to the Zgeiru that the revolution would have to confine itself, for now, to the South, where it had broad popular support. The "Free Republic of Huyfárah" was proclaimed in Miədu, in 567. The Republic assumed control of Kasca, the southern coastal colonies, Dagæm and the Southern Isles.

The political schism was mirrored in a religious one. Originally the revolutionaries had no intent of withdrawing their religious allegiance from Ussor, but soon they gave way to the repeated Fáralo tendency to use their religion as a tool of the state. Several high-ranking priests were dismissed, and a separate Great Temple was established in Miədu. Etúgə was split in two.

Mennat's forces and court were driven continuously eastward by Jorinago, with some help from the Republic. In 575 he fled with a sizeable force to Dagæm. This began the third phase of the war, largely consisting of naval battles against the Republic. Mennat took control of Dagæm, then invaded the Southern Isles, and proclaimed a "Kingdom of the Isles" ruled from Agumosou.

Meanwhile, Jorinago was unable to negotiate a successful arrangement to re-integrate the Republic, so he half-heartedly declared war; the Republic allied with Lasomo and was victorious, the two dividing the western marches between them. Republican support had waned in Mæmedéi; the city was retaken by force, and its government repopulated with political allies.

By now the nation was - or rather the two nations were - too exhausted to carry on the fight; peace was declared in 584.

Jorinago had himself re-crowned in a large ceremony in Ussor, and toured around the countryside, but the nation he presided over was in shambles: garlands and colorful banners were being strewn over burnt ruins. But the country was soon invigorated, as it periodically was, by a new religious revival - this time, mournful and Epimethean in nature, reflecting on fallen glories and preaching coming destruction. Macabre parades of mourners marched through the cities, painting their faces white, weeping and laughing hysterically.

The nation, even after accounting for territorial losses, had lost perhaps a fifth of its population, and its borders had shrunk essentially to the long, narrow strip of fertile land between the Oltu Valley and Čisse. The destruction was worst in the countryside, particularly in the heartland, which suffered from famine and disease for the next decade.

The Fáralo acted with unity of purpose in rebuilding their nation - but without unity of organization. While the contenders in the long war had fought for control of the whole nation, the fighting itself had ironically revealed the people's chief allegiances as being local and regional. The Empire itself had been discredited as an institution, and much of the rebuilding and reorganizing in this period was the work of minor nobles.

Lewsfárah

But the empire's new rival was hardly robust. Initially it appeared it would crumble amid infighting between various political factions. Chiefly the conflict was between the Zgeiru, now representing the mainstream, and a loose network of anarchist and anti-clerical elements, partially descended from the apocalyptic cultists who had emerged during the war. This latter faction was known as lu-Zjægə, "the wrathful ones."

The cities of Lewsfárah - "free-Fárah," as the Republic was informally known - experienced bouts of urban warfare for a decade. But soon the forces of order prevailed, and the Zjægə leaders were executed en masse .

The urban Toło population had been instrumental in supporting the Zgeiru, who repaid them with full citizenship under the new constitution. The Toło began to play a major role in the public and political life of the Republic. Their religion originally had been oriented, by necessity, around the concepts of secrecy and imminent divine vengeance; gradually it now drifted in doctrine and aesthetics back in line with Etúgə, though retaining a certain mystical air.

The climate of the Empire had been generally one of religious freedom, if somewhat inconsistently and at the whim of individual governments. The Republic, for all its egalitarian airs, actually took a step away from this: only Etúgəists could be citizens. (Epɨmya was simply reclassified as a "brother sect" of Etúgə.)

The new nation was organized as a federation of three city-state republics - Miədu, Azbǽbu, Mæmedéi - under the umbrella of a single government, with Miədu as the de facto capital. The federal government administered the peripheral territories: parts of Kasca, and the southern coastal colonies. The Republic's position was strengthened by alliance with Buruya and Lasomo; this was often called the Etúgə League, representing their claim to be the new, true masters of the faith.

Lasomo was a moderately powerful nation in its own right, and boasted a sophisticated and literate culture; its inclusion in the League guaranteed massive cultural cross-exchange with the Fáralo sphere. Among the most interesting results was that Lewsfárah (and Buruya) abandoned the old Fáralo calendar, instead switching their dating system to the Year of the Prophet. Meanwhile, Lasomo adopted the Fáralo eight-day week.

The official language of Lewsfárah was Fáralo, but increasingly this was a Fáralo that used distinctively southern grammatical forms, vocabulary and pronunciation. What evolved as the standard was essentially a compromise dialect with features of the three main cities. It was still quite conservative compared to vernacular speech.

The Republic had little interest in ruling the Kascan Delta, and let it go its own way. Ñolo was absorbed by Buruya, while the Republic maintained control of Puwa and the barrier islands, both now mostly Fáralo-speaking.

The New Nations

Lewsfárah saw itself as being sustained by a kind of ferocious spiritual resolve; to any outsider it was clear that its strength was an economic one. It stood at the nexus between land routes to the west and sea routes to the south, and had use of what had been the best shipbuilding facilities in the Empire, and several of the best harbors. Soon the Republic assumed the old Imperial project of colonizing the South Coast (that is, south of Kasca). This was a project that had dragged on with a feeling of permanence for centuries, but now had stagnated: the inherited colony consisted of a string of fortified outposts connected more to the motherland than to each other, producing little, ruling over little more than the strip of beach, looking away from the wild forested interior which lay outside its grasp.

The Republic moved many colonists into the existing towns, and established a new capital, called Lu-Alégadu (elided in the local dialect to Lalegdu or Laleddo), "Constitution." Soon the influence of the state began creeping inland.

The obvious stumbling-block for the Republic was the Maléi rump state, the Kingdom of the Isles. This was a grim Fáralo oligarchy ruling over a Komejech- and Peninsular-speaking serfdom. Mennat's successors were petty and capricious, some outright insane. They maintained order brutally, and the kingdom drifted into political isolation. Within a couple generations authority had broken down and the islands became a haven for pirates, an anarchic land of warlords with nominal allegiance to a mad king who sometimes called himself "emperor."

The pirate bands were ethnically quite diverse, claiming members from among all the seafaring peoples - Takuña, Fáralo, Doroh, Affanonic, Lotoka, Sošunami - but the lingua franca was a form of Takuña.

The Republic invaded Dagæm in 638, quickly subduing it, then proceeded to the Southern Isles. The king was routed easily; many of the pirates, after a bloody struggle, were chased northward, into Imperial waters. They established various footholds within Huyfárah, east of the Poráš river.

The empire's institutions were atrophied, the Navy ineffective; the pirates - usually known as "the Takuña" - could not be dislodged. Strengthened by new arrivals from the east, they became entrenched in the area, right within the Fáralo heartland. The empire's old ally Affalinnei had for centuries acted as a buffer against pirates from the east, but it too was under control of Takuña bands.

The Doroh lords were unsettled by this shift in the balance of power. Previously disunified, they solemnly established an alliance (soon including Affalinnei as well), and drove the Takuña from their lands. The Takuña, in turn, invaded Čisse in 644.

Lewsfarah's merchant marine avoided these pirate-infested waters by making the eastward crossing directly from the Southern Isles to trade with Sumarušuxi. The Sošunami League was in a period of disunity, and Lewsfárah's commercial expeditions in the area soon led to an involvement in local political disputes; little by little, this involvement blossomed into a colonization of much of the area. The Republic now in effect controlled trade across the entire Bay of Kasca.

The Age of Three Leagues

The new ruling dynasty in Huyfárah, the Sattek, was bent on restoring absolute rule, and did so without any sense of moderation or judiciousness. The crippled Empire in effect wasted its remaining energy oppressing its own people and brutally crushing even the most innocuous forms of dissent. The next century and a half consisted essentially of a power struggle between three political blocs attempting to digest what they could of the crumbling state.

The first bloc was the Doroh-Affalinnei league, known as the Kørjah (Tøm. "league; alliance"). Its raison d'être was to repel pirate attacks and ensure free trade in the region; in effect this resulted in a gradual absorption of Fáralo areas for "defensive purposes." Its internal structure was decentralized and complex to the point of impenetrability, being based on various reciprocal agreements between the clans. Nonetheless, the effective center of power was one coastal Doroh city-state, Ẓaṛmott, on Bafyr Island. Its dialect, Ṭømjuñar, gained a level of prestige in the region.

Čisse threw off its Takuña overlords in a popular uprising in 655. The locals elected to set up an autonomous republican government. The various factions within the Empire, meanwhile, were unable or unwilling to fight this latest secession. After hurried negotiations the government chose to align itself with its neighbors - the Kørjah.

The second bloc, the Sošunami League, was not an effective force until later in this period. Disunified and hobbled by tribal vendettas, it concentrated its efforts on a unifying cause: keeping the Fáralo away from their ancestral capital, Umuhètha, on Pikàthìnuṭu Island. As the Republic had taken over most of Ikím, their center of gravity shifted to Wihe.

The third bloc, of course, was the Republic and its allies - the "Etúgə league."

Dəiṭah sent a large invasion force right into the middle of Huyfárah, near Sertek. The Emperor, seeing that the Doroh intended to stay indefinitely, attempted to expel them, but they counterattacked, taking Peimast (672), then Sertek (678), and later Barnágo (702).

Meanwhile, Lewsfárah invaded the Oltumosou and the Kučil valley. The Fáralo there found themselves as colonial vassals of overseas powers - the Republic, for all its moralistic pretenses, ruled quite despotically.

Finally the Empire was left with only the lower Oltu and lands immediately to the east; often it was now referred to merely as "Ussor." The pirates had never quite been eliminated from the coast, and their power ebbed and flowed, supplanted periodically by new arrivals. The emperor remained in place by playing them and the Kørjah states against each other.

This situation remained stable for half a century: it was the height of Lewsfárah's influence and prestige. During this brief flowering it boasted perhaps the most sophisticated and literate culture in the world, envied and imitated all across the sea. Petty tribal states styled themselves as republics, and their chieftains as Etúgə scholars, learned and urbane men dedicated to peace and poetry.

End of the Empire

The Republic got into a scuffle with the Sošunami in the 750s, resulting in the latter taking back the southern half of Ikím island. A political reorganization following this defeat resulted in the overseas colonies being partitioned between the different “home cities,” with Miədu and Azbǽbu taking the lion’s share. But Mæmedéi administered over Oltumosou, and a few enclaves on the northern coast, east of Lotoka.

Where Miədu had once been first among equals, its power was increasingly checked by the senates of the other two cities. The sense of a unified standard language began to fray as each local government insisted upon the norms of its own city.

In 786 one Doroh band under the umbrella of the Kørjah, enforcing order in the rump imperial state under the increasingly abstract political fiction of “defending against piracy,” overwhelmed the city garrison and murdered the emperor. The new, post-imperial age was one of political repression, coupled with cross-cultural ferment. Various religions from the east made headway in the Fáralo heartland. One of these, Pa'en, the religion of the Takuña, had a largely-forgotten ancient kinship to Etúgə. It was known in Fáralo as Ku Mašonošin, "[Religion of the] Immortal Spirit."

Initial concerns within Lewsfárah about “anarchy” reached a fever pitch, resulting in a reinforcement of city defenses -- then were dismissed as counterrevolutionary or un-republican. The Republic agreed to recognize the Kørjah as the successors to the Fáralo state. Various loyalist social circles who had fled the collapsing empire now found themselves inside Lewsfárah, many clustered in Miədu around the residence of the pretender to the throne, a young playboy.

This imperial pretender, Sertačil (Nam. Settsił), gained influence in the city government, finally ascending to the powerful position of Deputy Mayor. In 795 the senate of Azbǽbu sent a resolution condemning this development as indicative of “un-republican sentiment.” Over the next three years the conflict escalated, nearly resulting in civil war, but the delegate from Mæmedéi brokered a peace deal resulting in Miədu's voluntary exit from the Republic. Miədu surrendered control of the Dagæm Islands, retaining the Southern Isles and the South Coast.

In 812 Mæmedéi and Azbǽbu parted ways, dissolving the Republic of Lewsfárah. All three cities remained within the Etúgə League, with the form of local government developing separately in each: In Mæmedéi the senate seats became tied to hereditary wealth, resulting in oligarchy; in Miədu the power of the Senate became eclipsed by popular allegiance to clerics and their enforcers, resulting in de facto theocracy; but Azbǽbu retained the original model of an elected legislature powered by a pious, industrious bourgeoisie.

Dark Ages

With the implosion of both Fáralo states the following generations are considered a dark age, with the corresponding shrinkage in population and local concentration of power. This was less a cataclysm and more a grinding stagnation, with a lack of intellectual development, and an unprecedented level of vagabondage and piracy.

The most powerful state in this period was Miədu, where the theocracy became explicit in 825 as the chief cleric was appointed Supreme Defender of the Faith, with power of veto over the Senate. Increasingly all strata of society were preoccupied with the irredentist goal of taking back the Dagæm Islands from Azbǽbu. This was mingled with the ancient pretext of "defense against piracy," awkwardly complicated by the fact that in many cases the "pirate" factions were intertwined with the navies of both cities. The Supreme Defender declared a kind of crusade, with mass conscription among the commoners. The resulting war with Azbǽbu (839-841) was destructive but short, resulting in Miəduan victory.

Oltumosou kicked free of Mæmedéi in 840, setting up a quasi-republican state headed by a “High Lord.”

A loyalist uprising in the Oltu Valley resulted in a massacre of the Doroh leaders and the establishment of the kingdom of Woldulaš in 843, centered in Ussor. The new state took Barnágo in 869. At this point no state in either the republican (or post-republican) South nor the monarchical north lay claim to the mantle of "Huyfárah" as such.

Both the Sumarušuxi and Kojroh Leagues had collapsed by 900 amid infighting, with the Fáralo states mopping up most of the gains. The Čisse-Affalinnei alliance held steady, while Mæmedéi’s old possessions in Siixtaguna came under the control of Oltumosou.

Another uprising against the Doroh in 890 resulted in a second Fáralo kingdom in the Poráš valley, modeled after Woldulaš, prosaically known in the local dialect as Bōskəlaš, “The Governorate.”

Čisse and Oltumosou tentatively formed a union in 909. In both cities the sense that the Fáralo were an Etúgə people had dissipated, and the dominant religion was now a form of the cult of the Affanonic sky god, Tejenry, syncretized with Pa’en.

Woldulaš flourished throughout the tenth century, but lacked in naval power. Officials there began strengthening bonds with their southern neighbor, the minor naval power of Mæmedéi, whose sailors were renowned as technically skilled, prudent, and level-headed.

West of the Fáralo sphere, the irredentist spirit reared its head in Lasomo, where the rulers dreamed of retaking the ancient capital, Akelodo — now the largest city in the Athalēran Empire, and probably on the continent. Much of the populace there, both urban and rural, had scorned the state religion of Anaitism in favor of the Etúgə faith of their northern neighbors. Where previously religious tolerance had flourished, the Anaitist rulers subjected the Etúgə to increasing persecutions — a counterproductive activity, as each wave of bloodshed led to a new generation of fanatics and martyrdom cults.

Sensing weakness in the ancient empire, as it struggled to put down rebellions across the land, the Lašomorans sponsored an Etúgə insurgency in Akelodo, who took the city in 971. When the Empire lay siege, Lašomo came to the rescue of the city. The resulting war between the two nations lasted five years, ending with the Republic (bolstered by the rest of the Etúge League) absorbing Akelodo and the remainder of Lašomo. The capital, for a time, remained at Oigop'oibauxeu (F. Boíəba, Ad. Ziphē), and the chief language a form of Ndok Aisô.

Also as a consequence of the war, Miədu established a puppet state within former Athaleran borders, on the lower Milīr, south of Lasomo.

The crippled Empire lived on for a generation, sloughing off outlying provinces here and there, until the bitter end came in 1003, with the partitioning of the core Dāiadak lands into a handful of different states, the most powerful of which was Thāras.

In Lašomo, the magnetic pull of the great metropolis of Akelodo lead to the capital relocating there in 1007, and the language of state shifting to the local dialect of Adāta, called Æðadĕ.

Tension between Miədu and the ascendant Lasomo lead to the dissolution of the nearly 500 year old Etúgə league in 1026. Lasomo expanded eastward into the Tal of western Huyfarah. Buruya developed as a regional military power, expanding downriver to capture the ancient town of Ñolo. Its major rivals in the delta were the towns of Luyoša and Mospiñor.

Woldulaš absorbed Mæmedéi in 1019, leading to the rise of the kingdom as a sea power.

Names

| Language | Name | Pronunciation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ndak Ta | Sau Ibli | [sau ˈib.li] | "North Coast" |

| Adāta | Hazīli | [ˈha.ziː.li] | ← NT Sau Ibli |

| Fáralo | Huyfárah | [hujˈfa.rah] | ← Far. Soifaragh "Faraghin Coast" (borrowed) |

| Naidda | Puivara | [ˈpuj.va.rə] | ← F. Huyfárah (borrowed) |

| Wippwo | Fuβera | [ˈfu.βɛ.ra] | ← Ndd. Puivara |

| Buruya Nzaysa | Xuyfá’ah | [xujˈfa.ʔah] | ← F. Huyfárah (borrowed) |

| Ndok Aisô | Hoifaxa | [hɔjˈfaː.ʔa] | ← F. Huyfárah (borrowed) |

| Mavakhalan | haźiľ | [ˈha.ʒiʎ] | ← Ad. Hazīli |

| Ayāsthi | ġàʒīly | [ˈɦɑ.ʒiː.lɨ] | ← Ad. Hazīli |

| Æðadĕ | Hæzili | [ˈhæ.zi.li] | ← Ad. Hazīli |

| Aθáta | Asíli | [aˈʒi.li] | ← Ad. Hazīli |

| Namɨdu | Hɨwora | [hɨˈwɔ.ɾɐ] | ← F. Huyfárah |

| Puoni | Rufara; Ragui | [rʊˈfa.rɜ], [rɜˈgwi] | ← F. Huyfárah, Hagíbəl |

| Woltu Falla | Hüfarā | [hyː.faˈɾɑː] | ← F. Huyfárah |

| Cəssın | Çarah | [ˈɕɑ.ɾɑx] | ← F. Huyfárah |

| Affanonic | Falarlinnei (esp. for the state); Falaril (esp. the territory) |

[fa.laʀ.ˈlin.nei], [ˈfa.la.ʀil] | derived from falar (adj.) ← Far. Faragh "the Faraghin people" (borrowed) |