Ndak Ta

| Ndak Ta [n̩ˈdɐk.ta] | |

| Period | c. -1900 YP |

| Spoken in | Kasca, Aiwa valley, Rathedān, Sau Ibli |

| Total speakers | c. 6 million |

| Writing system | adapted Ngauro script |

| Classification | Macro-Edastean Talo-Edastean Ndak Ta |

| Typology | |

| Basic word order | VSO |

| Morphology | mixed |

| Alignment | Split-S |

| Credits | |

| Created by | Radius |

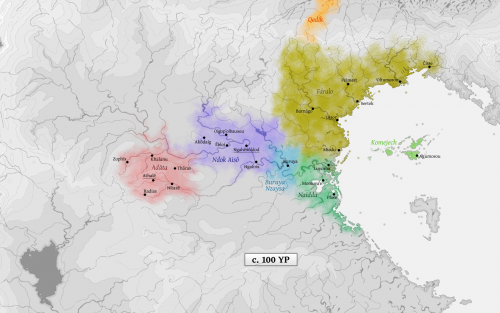

Ndak Ta is the language of the ancient Ndak Empire based in Kasadgad around -1900 YP. During the reign of emperor Tsinakan (r. -1915 to -1889 YP), the empire came to dominate the whole lower and middle Aiwa valley, the Rathedān highlands, and the coast up to the Čisse river in the north and the Şepamã river in the south. As a result, the Edastean language family descended from Ndak Ta became the most important linguistic group in north-central Peilaš for many millennia.

Genealogy

Ndak Ta itself belongs to the Talo-Edastean subbranch of the Macro-Edastean family. It is most closely related to Antagg, spoken on the upper Bwimbai, and Tlaliolz, spoken in the forest of Lu Tal. Another, more remote relative of Ndak Ta is Proto-Xoronic, the ancestor of the Habeo languages and Damak.

- Proto-Macro-Edastean (c. -3500 YP)

- Proto-Talo-Edastean (c. -2500 YP)

- Proto-Xoronic (c. -2500 YP)

Descendants

Ndak Ta is the ancestor of the Edastean languages, one of Akana's largest language families. It had six immediate descendants, the most important of which were Adāta and Fáralo.

- Western Edastean:

- Dāiadak languages: Adāta (Rathedān)

- Ndok Aisô (Axôltseubeu)

- Eastern Edastean:

- Fáralo languages: Fáralo (Huyfárah)

- Naidda (Kasca)

- Buruya Nzaysa (Buruya)

- Komejech (Dagæm islands)

- Northern Edastean

- Qedik (north coast)

Phonology

Phonemes and Orthography

Phoneme inventory

Consonants

| labial | alveolar | velar | labiovelar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain plosive | p | t | k | kʷ |

| voiced plosive | b · bʷ | d | ɡ | |

| affricate | ʦ | |||

| fricative | s | |||

| nasal | m | n | ŋ | ŋʷ |

| approximant | l | w | ||

| trill | r |

ORTHOGRAPHY:

- p t k kw /p t k kʷ/

- b bw d g /b bʷ d ɡ/

- s /s/

- ts /ʦ/

- m n ng ngw /m n ŋ ŋʷ/

- r l w /r l w/

When initial, final, or intervocalic, all of the above are always pronounced as shown. The only consonant allophony occurs in clusters (see cluster rules section below).

Vowels

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i · ɪ̃ | u | |

| mid | e · ɛ̃ | o | |

| low | a · ɐ̃ | ||

| diphthong | ai · ɐɪ̃ | au · ɐʊ̃ |

ORTHOGRAPHY:

- Oral: a e i ai au o u /a e i ɑi au o u/

- Nasal: â ê î âi âu /ɐ̃ ɛ̃ ɪ̃ ɐɪ̃ ɐʊ̃/

Syllable structure

There is a difference between what's phonetically syllabic and what the phonology treats as a syllable. The phonological rules of the Ndak Ta allow the following syllables:

- initial: (N)(C)V(C)

- medial: (C)V(C)

- final: (C)V(C)(N)

That is to say, a word may have nasal+consonant cluster initially or a consonant+nasal cluster finally, or both. From a phonetic standpoint, however, such initial and final clustered nasals are syllabic themselves. Some examples to illustrate...

- Legal words: [pap] [mam] [m=pap] [papm=] [m=papm=]

- Illegal words: *[pmap] *[pamp]

All of these legal words would be considered monosyllabic for stress rule and any other syllabification purposes.

Cluster Rules

Only two consonants per cluster, no more. These are treated as coda+onset in all cases except initially and finally, where clusters are disallowed except for nasal+stop and stop+nasal respectively (see syllable structure section above for more on that).

- NASAL+NASAL: All combinations allowed.

- STOP+STOP: All combinations allowed. The first stop assimilates to the voiced/voiceless value of the second (/t/ + /b/ becomes [db]).

- STOP+NASAL: Voiced stops assimilate into the corresponding nasal for their POA; if that matches following nasal, it results in a geminate. So /bama mba amba amab abm/ are all pronounced as shown, while /ab/ + /ma/ comes out as [amːa] (spelled amma) and /ad/ + /ma/ as [anma] (spelled anma). Voiceless stops before nasals all become [ʔ], such that /ampa/ = [ampa], while /ap/ + /ma/ = [aʔma].

- NASAL+STOP: Stops assimilate to the POA of the previous nasal: /an/ + /ba/ becomes [anda].

OTHER:

- /ʦ/ patterns as a stop.

- Liquids may cluster with all stops and nasals, or with /s w/ or each other, in either direction.

- /s/ assimilates to the voiced/voiceless value of any stop that follows it, but stops that preceed it become voiceless. /s/ remains voiceless when clustered with nasals or /r l w/.

- /r/ is pronounced [ɾ] when clustered with a labial or a velar, and [r] when clustered with an alveolar (including /l/).

- /w/ may follow any stop, nasal, liquid, or /s/.

- /kʷ ŋʷ bʷ/ are phonetically equivalent to [k ŋ b] + [w], but I'm analyzing them as seperate phonemes because unlike other sounds, these "clusters" can follow a consonant. Thus [mbw] or [skw] or [lŋw] are all legal clusters while, e.g., [mpw] is not, but it's easier to call these [w] combinations phonemes than to complexify the coda+onset analysis of clusters. They also behave like separate phonemes when on occasion a morpheme boundary may result in /kʷ ŋʷ bʷ/ being followed by a consonant, in which case the [w] vanishes and they become [k ŋ b] - and because some word-final [k ŋ b] become [kw ŋw bw] when a vowel is suffixed, but not others.

The epenthetic schwa rule: When adding a prefix or suffix would create an illegal consonant cluster, an epenthetic [ə] is inserted if the affix isn't a nasal that can become syllabic. An epenthetic schwa is always spelled as a and identified by speakers as belonging to the phoneme /a/. Since this epenthetic vowel is not contrastive, there is some variation as to whether it is added between the consonants in question or at the edge of the word.

Vowel Hiatus Rules

Vowel hiatus is generally forbidden. The first exception is that when the vowel combination matches one of phonemic diphthongs (/au ɑi ɐʊ̃ ɐɪ̃/), it becomes that diphthong. The second exception is when the vowel combination is one that naturally causes a glide sound to occur while moving from one articulation to the other; these "implied" consonants [j] and [w] are sufficient to allow the vowels to exist in quasi-hiatus.

For example, /oa/ and /io/ would be allowed, because they'd be pronounced [owa] and [ijo] respectively, while /ao/ and /ɛ̃a/ do not involve an intervening glide and are thus disallowed.

There may be some variation between speakers as to precisely which vowel combinations do and do not involve a glide.

When morpheme combinations cause illegal hiatuses to form, the first of the two vowels deletes.

Examples:

- /ba/ + /us/ = [baus] (hiatus becomes diphthong)

- /bi/ + /as/ = [bijas] (hiatus held apart by "implied" glide)

- /ba/ +/es/ = [bes] (full hiatus disallowed; first vowel deletes)

Vowel Allophony

Remember the nasal vowels? It may be helpful to not think of them as "main" vowels but instead allophones of the oral vowels that, whoops, became contrastive/phonemic in certain limited cases, c.f. German /x/ splitting into /χ/ and /ç/ in a tiny handful of minimal pairs. I'll explain how it came about and its implications in a moment.

There are two sets of allophones for five of the seven main (oral) vowels:

- /a e i ɑi au/ have the allophones of [ɐ ɛ ɪ ɐɪ ɐʊ] before a syllable coda.

- /a e i ɑi au/ have the allophones of [ɐ̃ ɛ̃ ɪ̃ ɐɪ̃ ɐʊ̃] before a nasal (whether that nasal is a coda or not).

The other two main vowels, /o/ and /u/, nasalize to [õ] and [ũ] respectively before nasals, but do not exhibit any other allophony.

The nasalized versions of the first five vowels have become contrastive. There used to be a fifth nasal consonant, /ɴ/. The usual vowel allophony applied before it, as before any other nasal; but /ɴ/ was lost after /a e i ɑi au/ and merged into /ŋ/ after /o u/. A cîrcûmflêx is used to mark that vowels formerly followed by /ɴ/ are still nasalized; all other nasalized vowels can predicted by seeing if it's followed by a nasal.

Examples:

- /pa/ [pa] pa

- /pan/ [pɐn] pan

- /paɴ/ → /pɐ̃/ [pɐ̃] pâ

- /poɴ/ → /poŋ/ [põŋ] pong

Stress Rules

Stress is usually on the first syllable of the word stem, regardless of inflections. Keep in mind that this applies only to vowel syllables; initial and final syllabic nasals do not count as "syllables" for stress purposes. A few words have stress on some other syllable instead; when stress is elsewhere, it is marked with a gràvè àccènt.

Ndak Ta is a syllable-timed language. That is, each syllable, not including syllabic nasals, is pronounced in roughly the same amount of time as any other; syllabic nasals just kinda get "squished" in between.

Grammar

Grammar Introduction

The most neutral overall word order in Ndak Ta is VSO; SOV also occurs, especially in certain types of clauses, and OVS is sometimes used as an alternate strategy to topicalize the sentence object (the main strategy being passive constructions) and for certain other specialized uses. Ndak Ta leans heavily towards head-initial constructions, or, put another way, is right-branching.

Verbs inflect for several tense-aspect combinations (nonpast, past imperfective, past perfective, pluperfect), voice (active, passive, middle), and a large number of moods. Nouns do not inflect, but they take determiners (including articles) which do inflect to show the case and number of the noun. The three cases are subjective, objective, and dative, and the three numbers are singular, dual, and plural.

The noun case pattern of Ndak Ta is mostly nominative-accusative, but a few common verbs follow an ergative-absolutive pattern instead (perhaps two or three dozen if Ndak Ta were ever to be fully described), and thus technically it is a split-S active language if you want to split hairs. Verbal morphology is thus far entirely regular; irregular verbs were originally intended but never implemented. Noun determiner inflections are also almost entirely regular - or at least, perfectly predictable if you know a bit of the sound change history (more information on which can be found in the Phonology section). Pronoun inflections are missing a chunk of the pattern that applies to nouns but are otherwise regular.

Noun Phrases

Basic NP Syntax

Noun phrases are fairly rigid about their internal ordering, being D-N-A-R-P (determiner, noun, adjective, relative clause, prepositional phrase), though N-A-R-P-D and P-N-A-R-D are also used, especially when a clause contains more than one complex noun phrase.

Determiners

From a grammatical standpoint, the category of 'determiners' includes articles, demonstratives, and quantifiers. Every common noun must have exactly one of these. They inflect to mark their head noun's case and number, and unlike all other noun modifiers, they come before their nouns. Possessives are semantically determiners, but they can't carry determiner inflections, so an appropriate article is brought in for them. Usage note: there are two indefinite articles. The discourse-oblique indefinite article is used to mention nouns that will not figure largely in the following subject matter, while the discourse-referential article is used to introduce nouns that will.

| Articles | ||

|---|---|---|

| lu | Definite | |

| au | Indefinite discourse-oblique | |

| ndo | Indefinite discourse-referential | |

| Demonstratives | ||

| wai | Near-me | |

| gâ | Near-you | |

| tsi | Far-from-either | |

| General quantifiers | ||

| ngwa | (a) few | |

| namê | some, more than one | |

| omba | many | |

| ais | a large number of | |

| mi | no, none of | |

| ewe | all, every | |

| or | each one of | |

Determiner Suffixes

| SUBJ | OBJ | DAT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| singular | -∅ | -ng* | -m |

| dual | -g | -s | -ndi |

| plural/mass | -k | -s | -nti |

- The singular objective ending is -ng after /o u/ and the nasal form of the final vowel otherwise. For stems ending in consonants other than /k ɡ/, the epenthetic (nasal) schwa lowers to /ɐ̃/.

A note on case usage: the subjective and objective cases are equivalent to nominative and accusative for most verbs, but for ergative verbs, mark ergative and absolutive respectively.

NP Examples

"Luk ailàu are pretty."

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- ailàu

- ailàu

- flower

"Lu asa isn't here."

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- asa

- asa

- woman

The distinction between the demonstratives is glossed with 1, 2, or 3 - 1 being "near me" (first person-like), 2 being "near you" (second person-like), and 3 being "far from either of us" (third person-like).

"I like wâi ailau."

- wâi

- wai-ng

- DEM1-OBJ.SG

- ailàu

- ailàu

- flower

"Tsi asa likes me."

- tsi

- tsi-∅

- DEM3-SUBJ.SG

- asa

- asa

- woman

"I don't like tsis rud"

- tsis

- tsi-s

- DEM3-OBJ.PL

- rud

- rud

- man

"Ewek rud are created equal."

- ewek

- ewe-k

- all-SUBJ.PL

- rud

- rud

- man

"Ewek maldo are created equal."

- ewek

- ewe-k

- all-SUBJ.PL

- maldo

- maldo

- person

"I gave ngwanti maldo my number."

- ngwanti

- ngwa-nti

- a_few-DAT.PL

- maldo

- maldo

- person

"I gave gânti asa namês ailau"

- ganti

- gâ-nti

- DEM2-DAT.PL

- asa

- asa

- woman

- namês

- namê-s

- some-OBJ.PL

- ailàu

- ailàu

- flower

Now let's look at the two indefinite articles. Remember, the discourse-referential article ndo is used to introduce nouns that will be mentioned again later, while the discourse-oblique au identifies nouns that will probably be referred to only that once.

"I was satisfied the bill was correct only after asking âu rud from the company about it."

- âu

- au-ng

- INDEF(OBL)-OBJ.SG

- rud

- rud

- man

"I met ndong rud last night who was very nice. He..."

- ndong

- ndo-ng

- INDEF(REF)-OBJ.SG

- rud

- rud

- man

Personal Pronouns

Pronoun Table

| SUBJ | OBJ | DAT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Person i- | |||

| singular | i | î | im |

| dual | ig | is | im |

| plural/mass | ik | is | im |

| 2nd Person do- | |||

| singular | do | dong | dom |

| dual | dog | dos | dom |

| plural/mass | dok | dos | dom |

| 3rd Person a- | |||

| singular | a | â | am |

| dual | ag | as | am |

| plural/mass | ak | as | am |

| 2nd Person Formal laingko- | |||

| singular | laingko | laingkong | laingkom |

| dual | laingkog | laingkos | laingkom |

| plural/mass | laingkok | laingkos | laingkom |

Pronoun Usage Notes

Possessives: there are no explicitly possessive pronouns, but the effect can be achieved by compounding the preposition âk, equivalent to English "of" as regards possession, to the pronoun. Thus âki would be 1SG possessive, and âgdog 2DL possessive. When they are used attributively, these possessives are often inflected to agree in case with the possessed noun phrase (which is unexpected because âk on its own usually requires the possessor to appear in the subjective case).

Reflexives: there are also no reflexive pronouns, as reflexivity is handled with verb morphology, but in idiomatic speech a speaker often superfluously uses the objective form of the pronoun in addition to the subject form, the equivalent of saying "I wash.REFL me" even though "I wash.REFL" is grammatically sufficient by itself.

The dual number is not used to refer to just anything that happens to be two in number. It is used only for things one would normally expect to find in pairs: hands, eyes, shoes, couples, twins, etc., and single objects that consist of two like parts working together or in opposition, such as tongs, scissors, or bicycle wheels. If you used the first person dual, you could only be referring to yourself and your spouse as a couple (or possibly yourself and your twin sibling); to refer to yourself and any other person or group of people that might or might not include your spouse (or twin), use the plural. The same goes for determiner inflections.

The formal 2nd person is often used when speaking to one's elders and anyone higher than one on the social pecking order, which might be hard for non-natives to judge. It indicates a level of respect about equivalent to the use of "sir" in English, but it is never rude to use the "familiar" pronoun instead, not even with one's rulers. It would be better to use the familiar even to someone you respect than to risk awkwardness using the formal pronoun where it's not certain to be taken well, as it often implies a form of warm respect that might not be be well-received in all contexts. Paradoxically, the formal pronoun is always used in speech to any audience large enough that their anonymity to you would be normal.

Pronoun Examples

"I sent â to dom."

- Pilain

- pilai-n

- send-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- dom

- do-m

- 2-DAT

- â.

- a-ng

- 3-OBJ.SG

"Dok sent as to im."

- Pilain

- pilai-n

- send-PST.PFV.SG

- dok

- do-k

- 2-SUBJ.PL

- im

- i-m

- 1-DAT

- as.

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

Note how Ndak Ta typically puts the (dative) recipient before the (objective) theme in ditransitive sentences.

The following example shows both the dual number and how to form "possessive pronoun" constructions for the first time.

- Odgabmandi

- odgabm-ndi

- suffer-NPST.DL

- lug

- lu-g

- DEF-SUBJ.DL

- ton

- ton

- hand

- âki.

- âk-i-∅

- POSS-1-SUBJ.SG

Correlative Pronouns

| query | this | that | yonder | some | no | every | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| determiner | iwa | wai | gâ | tsi | namê | ma | ewe |

| thing/person | gewa | waige | gâge | tsige | nambe | mage | ege |

| place | mala | wailul | gâlul | tsilul | namlul | malul | elul |

| time | sola | waitsau | tsitsau | nambau | matsau | etsau | |

| way | ipa | tsip | namip | mip | ewip | ||

| reason | nduwa | tsindu | nambu | mandu |

Verbs

Tense, Number, and Voice Suffixes

Number is agreed with only for third person. 1st and 2nd persons both use the 'singular' forms. Dual number is agreed with only in the nonpast tense, and in the past perfective tense with ergative verbs in intransitive sentences. As all suffixes, these follow the epenthetic schwa rule when they would otherwise result in an illegal cluster.

| SG | PL | DL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| nonpast | -∅ | -n | -ndi |

| past perfective | -n | -be | -be(di*) |

| past imperfective | -sti | -s | -s |

| pluperfect | -da | -owa | -owa |

| infinitive/gerund | -∅ | ||

- *There is a -bedi dual past perfective that is still used with ergative verbs, generally only in intransitive sentences.

Voice

Voice suffixes are -l- for passive and antipassive, and -kin- for middle/reflexive. These follow the stem and come before the tense/number suffix. In both cases, if they cause an illegal final cluster, the epenthetic schwa rule is invoked.

Examples

In these examples we leave English and its word order behind and start using VSO as Ndak Ta sentences are supposed to be.

- Tsin

- tsin-∅

- like-NPST.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- â.

- a-ng

- 3-OBJ.SG

- Tsinandi

- tsin-ndi

- like-NPST.DL

- ag

- a-g

- 3-SUBJ.DL

- î.

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- Tsinan

- tsin-n

- like-NPST.PL

- ik

- i-k

- 1-SUBJ.PL

- as.

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

- Tsinan

- tsin-n

- like-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- as.

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

In the following two examples, note that 'grass' and 'meat' are mass (non-count) nouns and thus take plural number, unlike English where they would be singular.

- Narnosti

- narno-sti

- cut-PST.IPFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- empi.

- empi

- grass

- Tuda

- tu-da

- eat-PLUP.SG

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- sa.

- sa

- meat

Mood Prefixes

There are thirteen morphological moods in Ndak Ta, quite a large number. Some of them have multiple meanings which only context can make clear. I never got around to describing their usage in depth. They are prefixed to the verb stem.

| prefix | mood |

|---|---|

| ∅- | indicative ('He does it') |

| e- | imperative ('Do it') |

| m- | negative ('He does not do it') |

| is- | hortative ('Let us do it') |

| uk- | optative, volitive ('He would like to do it') |

| we- | futurative ('He will do it') |

| bwa- | probabilitative, permissive ('He may do it') |

| ngwi- | superprobabilitative, admonitive ('He probably does it', 'He should do it') |

| tso- | hyperprobabilitive, obligative ('He must have done it', 'He must do it') |

| ol- | reputative ('He is supposed to do it') |

| ru- | habitive ('He is accustomed to doing it') |

| idr-* | approximative, futilitive ('He seems to do it', 'He tries to do it' - without the speaker's expectation of success) |

| pâu- | conditional ('He would do it' - condition clause must follow) |

- *The approximative/futilitive mood prefix also occurs in the variant form er- in some dialects.

Examples

The same examples as before, nearly, but in various non-indicative moods.

- Matsin

- m-tsin-∅

- NEG-like-NPST.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- â.

- a-ng

- 3-OBJ.SG

- Wetsinandi

- we-tsin-ndi

- FUT-like-NPST.DL

- ag

- a-g

- 3-SUBJ.DL

- î.

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- Uktsinan

- uk-tsin-n

- OPT-like-NPST.PL

- ik

- i-k

- 1-SUBJ.PL

- as.

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

- Ngwitsinan

- ngwi-tsin-n

- ADM-like-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- as.

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

- Idranarnosti

- idr-narno-sti

- FUTIL-cut-PST.IPFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- empi.

- empi

- grass

- Oltuda

- ol-tu-da

- REP-eat-PLUP.SG

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- sa.

- sa

- meat

Participles

Participle forms are used only for deriving adjectives from verbs. This is done simply by using adjective morphology on a verb, which may optionally be inflected for mood and voice. Active participles are used for head nouns agentive of the action expressed by the participle, and passive participles for head nouns patientive of the action expressed by the participle. The rule is simple: if the situation described the the noun + participle construction would be subject + verb in a sentence, it uses the active participle, and if it would be verb + object in a sentence, the passive participle. The passive participle lines up nicely with English past-participial adjectives. Example: in "the frightened child", the child has received fright and thus the verb for 'frighten' would be formed as a passive participle. The active participle is somewhat equivalent, but less so, to the English present participial adjectives; it also fills the role of English agentive -er. Ndak Ta would say "the killing man" anywhere English would say "the killer" or "the man who kills". There is also a middle participle, -kintsa, not often used.

See adjectives section below for examples of participle use.

The Copula

The copula is a verb that inflects like any other, but it has no stem. It is a zero morpheme. This results in a word that consists entirely of inflection (a mood prefix or a tense/number suffix or both or neither); for instance, /s/, /bɛ̃/, /wɛ̃/+/ndi/, /m/+/owa/, and // are all forms the copula may take. Predicate nouns take the objective case. The fun part is that predicate adjectives, as one might expect, are placed in the object position in the VSO word order. This means that in some instances, since adjectives used attributively also follow their head nouns and especially where the copula consists of nothing at all, there may be ambiguity over whether the adjective is being attributed or predicated. If necessary it's possible to rearrange word order so that a predicate adjective preceeds the copula (see note about OVS order in the Introduction section), but speakers don't generally bother unless the distinction is important. One should note that the copula used to be /ɴ/, syllabic when standing alone, and that therefore the mood prefixes ending in vowels all end in nasal vowels when used in a copula; while after the mood prefixes tso and ru a copula stem still exists, realized as /ŋ/. Refer to the Phonology section for more on the former /ɴ/.

Examples of Predicate Nominals

- ∅

- ∅

- COP

- I

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- ndong

- ndo-ng

- INDEF(REF)-OBJ.SG

- rud.

- rud

- man

- Olna

- ol-∅-n

- REP-COP-PST.PFV.SG

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- imai

- imai

- name

- âka

- âk-a-∅

- POSS-3-SUBJ.SG

- Balau.

- Balau

- Balau

See adjectives section below for examples of predicate adjective constructions.

Adjectives

Adjective Morphology

Adjective morphology is simple, but there is quite a lot of dialectal variation.

Most commonly, adjectives agree with their head nouns for number; the agreement suffix is identical to the objective case suffixes for determiners (-ng* for singular, -s for dual and plural). The singular ending is often omitted though, especially with adjectives that end in a consonant. Leaving out the plural suffix as well is rare, but attested. (Notably, all adjectives in the Tsinakan text are uninflected, with no agreement at all.) On the other hand, there are also dialects which use the full determiner agreement system also on adjectives, with agreement not only for number but also for case (subjective vs. objective vs. dative).

Adjectives also take the suffix -in for positive comparatives and superlatives and -ur for negative comparatives and superlatives. These affixes follow the word stem and precede the agreement suffix. These forms exist alone for comparatives, and with the adverb newe meaning "most" for superlatives. The prefix m- negates the adjective.

Examples

Attributive Adjectives

Attributive adjectives follow their head nouns.

- Tsin

- tsin-∅

- like-NPST.SG

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- asa

- asa

- woman

- ilmong

- ilmo-ng

- beautiful-SG

- î.

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- Inan

- ina-n

- see-PST.PFV.SG

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- daing

- daing

- mountain

- pais.

- pai-s

- big-PL

- Inan

- ina-n

- see-PST.PFV.SG

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- daing

- daing

- mountain

- painsa

- pai-in-s

- big-COMP-PL

- newe.

- newe

- most

Predicate Adjectives

A "∅" indicates a copula that has no inflection and is thus not morphologically expressed. Note the epenthetic schwa rule in action in the second and third examples.

- ∅

- ∅

- COP

- Lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- asa

- asa

- woman

- ilmong.

- ilmo-ng

- beautiful-SG

- An

- ∅-n

- COP-NPST.PL

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- asa

- asa

- woman

- ilmos.

- ilmo-s

- beautiful-PL

- Idras

- idr-∅-s

- COP-PST.IPFV.PL

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- asa

- asa

- woman

- ilminsa.

- ilmo-in-s

- beautiful-COMP-PL

Participial Adjectives

For brevity I'll give only noun phrases with participial adjectives; these noun phrases fit into sentences the same way as any others. I'm assuming they're all subjects. Note how modal prefixes can still be used, with interesting effects.

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- aunti

- aunti

- river

- lailâ

- lail-ng

- flow-PTCP.SG

- ndo

- ndo-∅

- INDEF(REF)-SUBJ.SG

- dempi

- dempi

- child

- unmâ

- unma-ng

- play-PTCP.SG

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- rud

- rud

- man

- ngangong

- ngango-ng

- laugh-PTCP.SG

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- netrai

- netrai

- wife

- amraulâ

- m-raula-ng

- NEG-love-PTCP.SG

- âgdo

- âk-do-∅

- POSS-2-SUBJ.SG

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- sa

- sa

- meat

- wetulsa

- we-tu-l-s

- FUT-eat-PASS-PTCP.PL

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- rud

- rud

- man

- ngwidesmogng

- ngwi-desmog-ng

- ADM-hunt-PTCP.SG

Cases, Prepositions, and Their Usage

Theta Roles

Theta roles typically expressed by each of the cases:

- Subjective case: agent, force, experiencer

- Objective case: patient, instrument, experiencer

- Dative case: recipient, destination, goal, patient

Experiencers: This works like English for the accusative verbs, but be aware that ergative verbs (they are explicitly marked "ergative" in the lexicon) always put experiencers in the objective case.

Instruments and Patients: This is rather different from English. Where we would say "I hit it with a hammer", Ndak Ta would say "I hit it(DAT) a hammer(OBJ)". When there's an instrument, it gets the objective case and the actual patient gets the dative case. The same applies if the subject causes someone else to do something: where English would say "I made him kill it", Ndak Ta would say "I killed it(DAT) him(OBJ)" as if "him" was an instrument used to do the killing. Similarly, if a sentence puts a patient in the dative and does not mention anything with the objective case, it refers to indirect causation, like English "I had it killed".

- Wapan

- wapa-n

- hit-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- am

- a-m

- 3-DAT

- âu

- au-ng

- INDEF(OBL)-OBJ.SG

- batsn.

- batsn

- stick

- Engkun

- engku-n

- kill-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- lum

- lu-m

- DEF-DAT.SG

- tsis

- tsis

- dog

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- rud.

- rud

- man

Relational Prepositions

| âk | genitive (possessor, source), agentive (in passive constructions, like English "by"), initiative ("since") |

| wau | benefactive (purpose), "for", "concerning", "with respect to" |

| nte | adverbial (manner, as in "he sent it with love") |

| um | compositive (like 'a pile of bricks') |

| ngu | appositive, essive ("as") |

| kwen | comitative ("with") |

| al | abessive ("without"), "besides", "except for" |

| puk | "per", "for each" |

Locative Prepositions

| sa | elative ("from out of") |

| nai | inessive ("in") |

| anda | illative ("into") |

| uwa | ablative ("from", "from near", "after") |

| ob | adessive ("at", "near to") |

| isla | allative ("to", "towards", "before"/"by" for time) |

| nggairit | terminative ("as far as", "as much as", "until") |

| rambe | prolative, prosecutive ("along", "via", "during") |

| mbembu | interessive ("between", "among") |

| lita | ("throughout") |

| ntatsn | ("surrounding", "all around") |

| rigng | ("across", "in spite of") |

Prepositional Phrase Syntax

The word order is P-NP - that is, first preposition, then the noun phrase it applies to. The same rules apply to noun phrases here as anywhere else. Prepositional phrases are always modifiers to some other sentence element, be it noun or verb. In noun phrases they typically follow all other constituents of the phrase. If they modify the verb, they most often come at the very end of the sentence, but sometimes they are used at the beginning before the verb instead, a matter of style choice. Using such an adverbial prepositional phrase before a verb tends to emphasize it somewhat.

Case Governance

- The locative prepositions anda, isla, and nggairit govern the dative case for the noun phrases they take.

- The other locative prepositions govern the objective case.

- The relational prepositions govern the subjective case most of the time, but sometimes objective case if the speaker wishes to emphasize the noun. For instance, âk lu diàka "of the king" is neutral, while âk lung diàka is equivalent to English "of the king" (i.e., the king and not something or someone else).

Clause Syntax

Complement Clauses

These are clauses used as an argument of the verb (a subject, object, or indirect object), or as the object of a preposition. Some verbs can or must take whole complement clauses as one or more of their arguments. The complement clause is subordinated with the nominalizing conjunction rai, which comes at the beginning of the clause, and to which a case marker from the 'singular' row in the noun case table is suffixed: nothing for subjective case, -ng for objective, and -m for dative. This marks the role that the complement clause as a whole takes in the sentence. Complement clauses take finite or infinitive verbs as appropriate to the construction. Word order within a complement clause is VSO, and aside from the complementizer rai, a complement clause could usually stand on its own as a sentence.

- Mbin

- mbi-n

- say-PST.PFV.SG

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- râi

- rai-ng

- CMPL-OBJ

- raula

- raula-∅

- love-NPST.SG

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- î.

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

Adverbial Clauses

Adverbial clauses are adjunct clauses that, rather than being an argument of the verb, just add extra information. These take three forms: prepositional phrases (the use of which is previously described), complement clauses used as the object of a preposition, and embedded adverbial sentences. The latter are subordinated with the conjunction raits at the beginning of the clause, similarly to complement clauses, but unlike those, adverbial clauses normally take the word order SOV. All adverbial clause types can come either at the end of the sentence, or at the beginning.

The first example shows an adverbial prepositional phrase. Note: "to fall" is an ergative verb and thus takes an object, not a subject. Also note that the locational preposition anda governs the dative case.

- Endun

- endu-n

- fall-PST.PFV.SG

- î

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- anda

- anda

- into

- lum

- lu-m

- DEF-DAT

- aunti.

- aunti

- river

The following example is more complex, with the same prepositional phrase placed inside a complement clause which is itself the subject of a causative construction:

- Emburna

- embur-n

- swim-PST.PFV.SG

- rai

- rai-∅

- CMPL-SUBJ

- endun

- endu-n

- fall-PST.PFV.SG

- î

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- anda

- anda

- into

- lum

- lu-m

- DEF-DAT

- aunti

- aunti

- river

- im.

- i-m

- 1-DAT

The next example shows an adverbial clause that is formed by using a complement clause as the object of the preposition nggairit "until", which governs the dative case.

- Tsoseman

- tso-sema-n

- OBL-wait-NPST.PL

- ik

- i-k

- 1-SUBJ.PL

- nggairit

- nggairit

- until

- raim

- rai-m

- CMPL-DAT

- woto

- we-oto-∅

- FUT-come-NPST.SG

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- diàka.

- diàka

- king

The last example presents the third type of adverbial clause, an embedded sentence with the conjunction raits and SOV word order. This type of clause typically stands on its own, but it may occasionally also appear as the object of a preposition.

- Raits

- raits

- CMPL.ADV

- ak

- a-k

- 3-SUBJ.PL

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- ton

- ton

- hand

- âkas

- âk-a-s

- POSS-3-OBJ.PL

- sâpabmas,

- sâpabm-s

- lift-PST.IPFV.PL

- kaktodbe

- kaktod-be

- greet-PST.PFV.PL

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- rud

- rud

- man

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- diàka.

- diàka

- king

Coordinate Clauses

Rules

Coordinated clauses are two or more clauses that would be able to function independently as sentences, linked by various coordinating conjunctions describing the relationship between the clauses. However, elements are often omitted from them, or "gapped", to avoid overrepetition of content words. Gapping is governed by the following rules:

- a coordinated clause missing a subject is assumed to have the same subject as the previous clause.

- a coordinated clause missing a direct and/or indirect object is assumed to not have any, unless a special conjunction is used, as per:

- special forms of the conjunctions exist that cause all object gaps in the coordinated clause to refer to the same objects of the first clause.

- Unlike English, verbs cannot be gapped. However, the pro-verb su (somewhat equivalent to English "do") can be used. For instance, where English can say "I like you, and he me", the second clause gaps the verb; Ndak Ta would have to say "I like you, and he does me". The proverb can inflect like any other for mood, tense, and number.

Coordinating conjunctions

| on | and | ("I like him, and he seems trustworthy") |

| dal | but | ("I dislike him, but he seems trustworthy") |

| mi | or | ("You can buy it with cash or charge it to your credit card") |

| gunto | so, thus | ("He seems trustworthy, so I agreed to lend him the money") |

| nin | therefore | (takes the place of English if/then. Where English says "if X then Y", Ndak Ta says "X nin Y") |

| boda | "exclusive or" | (takes the place of English either/or. Where English says "either X or Y", Ndak Ta says "X boda Y") |

| lik | nor | (takes the place of English neither/nor. Where English says "neither X nor Y", Ndak Ta says "X lik Y") |

Note that all of these can be used between noun phrases in addition to between clauses. The following list, however, cannot:

Object-Gapping Conjunctions

| ongwâ | and |

| daldâ | but |

| mit | or |

| gundâ | so, thus |

| nindâ | therefore |

| bodat | "exclusive or" |

| ligâ | nor |

Examples

Underscores _ are used to indicate gaps in the coordinated clauses. In parenthesis afterwards are given the pronouns that would appear there if they needed to.

- Ina

- ina-∅

- see-NPST.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- â

- a-ng

- 3-OBJ.SG

- on

- on

- and

- ina

- ina-∅

- see-NPST.SG

- _

- dong.

- do-ng

- 2-OBJ.SG

- (i)

- Ina

- ina-∅

- see-NPST.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- â

- a-ng

- 3-OBJ.SG

- ongwâ

- ongwâ

- and.GAP

- tsin

- tsin-∅

- like-NPST.SG

- _

- _.

- (i)

- (â)

The following example contains both an object-gapping conjuntion and the proverb su:

- Ina

- ina-∅

- see-NPST.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- dong

- do-ng

- 2-OBJ.SG

- ongwâ

- ongwâ

- and.GAP

- bwasun

- bwa-su-n

- PROB-do-NPST.PL

- nas

- nas

- maybe

- ak

- ak

- 3-SUBJ.PL

- _.

- (dong)

Relative Clauses

Relative clauses are embedded sentences that modify a noun or noun phrase. They are formed with a relative pronoun at the beginning of the clause, and a gap where the relativized noun would be. The word order within the relative clause is normally SOV, but may also be VSO, especially when the verb in the relative clause is the copula, or when all remaining core arguments within the relative clause are expressed by pronouns.

The relative pronoun is roma, and can be inflected with -ng or -m to indicate that the relativized noun is, respectively, a direct or indirect object within the relative clause (which is different from the role it plays in the main clause: compare "the man that I saw" with "the man that saw me"). The pronoun remains roma when the relativized noun is the subject of the relative clause.

- Tsinan

- tsin-n

- like-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- rud

- rud

- man

- româ

- roma-ng

- REL-OBJ

- inan

- ina-n

- see-PST.PFV.SG

- i.

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- Tsinan

- tsin-n

- like-PST.PFV.SG

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- rud

- rud

- man

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- inan

- ina-n

- see-PST.PFV.SG

- î.

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

Ergative Verbs

Ergative verbs work like other verbs in most ways, except that when used in intransitive sentences, the argument they take is normally an object, not a subject (but, either way, is always marked as an object). In an intransitive sentence, the argument of an ergative verb is nearly always a patient or experiencer, while the argument of an accusative verb never is. The passive/antipassive verb suffix -l switches this around so that ergative-antipassives take agentive nouns for subjects and accusative-passives take patientive nouns for objects in intransitive sentences.

To illustrate this, let's compare the verbs "to eat" and "to kill" (tu and engku). Tu is ergative while engku is accusative. Both can be used either transitively or intransitively. In transitive sentences, both work much like English: "I eat the food" and "He killed Mary" both have agents in the subjective case and patients in the objective case. When engku is used intransitively, we get a sentence like "he killed", in which 'he' is the agent of the killing. This applies to all accusative verbs. When tu is used intransitively, however, we do not get "I eat". Instead, the best translation into English would be "I am eaten"! It's the thing eaten that normally goes with this verb in an intransitive sentence.

Then we can change these around by adding the passive/antipassive suffix -l to the verb (before tense/number marking). This changes the above examples from "he killed" and "I am eaten" into "he was killed" and "I eat".

Derivation and Compounding

Zero Derivation

Most Ndak Ta derivation is "zero-affix", i.e. does not involve any additional morphemes.

- Verb -> Adjective - Done by means of participles as described previously. To recap, a verb stem inflects first for mood and/or voice, as applicable, then gets any applicable adjective suffixes, then is placed after the noun.

- Noun -> Adjective - The bare noun stem is placed after the noun it modifies, without any determiners of its own. Example: lu ngkai lai "the egg bird"; specifies that it's a bird's egg and not some other kind of egg.

- Verb -> Noun - I made a brief entry in the verb inflection table for gerunds, but didn't explain anything. The verb stem, which may be inflected for mood but nothing else, is simply treated as a noun in its own right, requiring a determiner. Note that nouns derived from verbs this way cannot take direct objects like English gerunds can; complement clauses must be used instead.

- Noun -> Verb - Practically any common noun can be verbed by inflecting the stem like a verb would be. However, this strategy is not often used.

- Adjective -> Verb - Some adjectives, particularly those describing a state that can be experienced by a person - cold, wet, happy, etc. - can be turned into verbs by adding the appropriate verbal morphology. However, verbs derived this way are always intransitive and, this is important, always ergative. Example: ngwolâin î uwa lung tu, full me after/from the eating: "I was made full from the eating".

Morphological Derivation

The suffix -bu turns a verb into a noun that is an agent or patient of the verb (like English -er and -ee rolled into one); typically refers to a subject if the verb is accusative and an object if the verb is ergative, but there are exceptions.

The suffix -lau means "place of" and can be applied to verbs or nouns, resulting in a noun that means "the place where X occurs/occurred" and "the place where X is/was" respectively.

The prefix umbom- is a type of causative; it turns an adjective into a verb meaning "to make X", for instance "to make blue". Not often used.

The suffix -le weakens verbs and adjectives, turning "blue" into "bluish" and "flow" into "trickle"; attached to nouns, it functions as a diminutive and familiarizer, and is often used with names of people. Whenever attached to a noun or name, any syllables after the first (or stressed) are omitted and -le attaches to the end of the first syllable. Extremly common.

Compounding

Not exactly rare, but not exactly common either. Can take either order; either head-modifier, or modifier-head, and speakers have to remember which way is meant for every compound. Compounding of more than two words is unattested.

By far the more common way to turn multiple words into single lexical items is via idioms and set phrases.

A Strange Particle

Watch out also for the category-defying particle ta. Yes, that's the same one that appears in the name of the language. It performs a function very much like a 'dynamic' aspect, and in fact imparts exactly that to verbs, but can be used to modify nearly any part of speech. So "to be" + ta = "to become", while "to have" + ta = "to get". Using it after the preposition isla, meaning "before" in the instance that shows up in the sample text, imparts a dynamic-like emphasis somewhat equivalent to English "even before". And the language name itself? Ndak is a noun. A proper noun; it's the name of the people who speak this language (and doesn't mean anything else, it's an unanalyzable ethnonym). Ndak Ta is, in a sense, the 'dynamic aspect' of the Ndak, which to them is the sum of their speech, way of life, and social interaction. It thus refers to both the language and culture of the Ndak. It can be used with plenty of other nouns too, but gives meanings that aren't always predictable. For instance maundi ta, "person"-dynamic, which doesn't appear in the text, refers to one's spirit and/or mind. Ta can modify nouns, verbs, adjectives, pronouns, adverbs, and prepositions. Despite this flexibility, it isn't hugely productive.

Sample text

- Main article: Tsinakan text

Text

Mbi tsip Tsinakan, ngu lu diàka peras, ngu lu diàka âk lu lats um Kasadgad, ngu lu merkàt âk Tol on Imbi:

Isla raits i ob lung ospàk âk lu mebwe âki mpen, isla im as ewek lats sai, selkon. Mbibe tsip luk lats sai roma an lus wimès âkis: "An lu mebwe âka ndong diàka peras. Sompìsna a ombas lats sai. Tsitsau, an ta a ndong naka. Dal lu maldo roma waitsau ob lung ospàk âk lu mebwe âka mpe, ndong dempi."

Sola i, ngu lu merkàt âk Tol on Imbi, ob lung ospàk âk lu mebwe âki mpen, isla ta nonan i isla lunti lats sai roma as selkon isla im, nonan i isla lunti bwaikti âk Ombàsi. Bwenggorna i as on sâpabman i lung ton âkî isla lum omo eptàg. Mbin tsip i: "Dasi âki, ngu lu tol âk luk bwai! Tsurtorbe luk lats roma an lus wimès âkis roma papaube î 'aum dempi' î. Tsitsau, paston ta ak lus kak âk lu lats dautin âklaingko, dasi âki! Esompìs lus mpurnim!"

Ranton Ombàsi lus lewai âk lu mabm âki. Ulan a im on tsampin a lum itwam âkim lus bambor. Rambe rong laid, sompìsna i tsis rai mâukowa î. Ebrin i as. Esulna i aus ngaktìs, baus, on gaibra, on pilain i as isla lum lats um Kasadgad.

Interlinear Gloss

- Mbi

- mbi-∅

- say-NPST.SG

- Say

- tsip

- tsip

- thus

- thus

- Tsinakan,

- Tsinakan

- Tsinakan

- Tsinakan,

- ngu

- ngu

- as

- as

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- diàka

- diàka

- king

- king

- peras,

- peras

- brave

- valiant,

- ngu

- ngu

- as

- as

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- diàka

- diàka

- king

- king

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- lats

- lats

- country

- land

- um

- um

- PART

- of

- Kasadgad,

- Kasadgad

- Kasadgad

- Kasadgad,

- ngu

- ngu

- as

- as

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- merkàt

- merkàt

- brother

- brother

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- Tol

- tol

- sun

- Sun

- on

- on

- and

- and

- Imbi:

- imbi

- moon

- Moon:

- Isla

- isla

- towards

- Before

- raits

- raits

- CMPL.ADV

- that

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- ob

- ob

- on

- on

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- the

- ospàk

- ospàk

- throne

- throne

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- mebwe

- mebwe

- father

- father

- âki

- âk-i-∅

- POSS-1-SUBJ.SG

- of me

- mpen,

- mpe-n

- sit-PST.PFV.SG

- sat,

- isla

- isla

- towards

- towards

- im

- i-m

- 1-DAT

- me

- as

- ∅-s

- COP-PST.IPFV.PL

- were

- ewek

- ewe-k

- all-SUBJ.PL

- all

- lats

- lats

- country

- lands

- sai,

- sai

- foreign

- foreign,

- selkon.

- selkon

- hostile

- hostile.

- Mbibe

- mbi-be

- say-PST.PFV.PL

- Said

- tsip

- tsip

- thus

- thus

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- the

- lats

- lats

- country

- lands

- sai

- sai

- foreign

- foreign

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- that

- an

- ∅-n

- COP-NPST.PL

- are

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- the

- wimès

- wimès

- neighbor

- neighbors

- âkis:

- âk-i-s

- POSS-1-OBJ.PL

- of us:

- "An

- ∅-n

- COP-PST.PFV.SG

- Was

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- mebwe

- mebwe

- father

- father

- âka

- âk-a-∅

- POSS-3-SUBJ.SG

- of him

- ndong

- ndo-ng

- INDEF(REF)-OBJ.SG

- a

- diàka

- diàka

- king

- king

- peras."

- peras

- brave

- valiant.

- "Sompìsna

- sompìs-n

- defeat-PST.PFV.SG

- Conquered

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- he

- ombas

- omba-s

- many-OBJ.PL

- many

- lats

- lats

- country

- lands

- sai."

- sai

- foreign

- foreign.

- "Tsitsau,

- tsitsau

- then

- Then

- an

- ∅-n

- COP-PST.PFV.SG

- became

- ta

- ta

- DYNAMIC

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- he

- ndong

- ndo-ng

- INDEF(REF)-OBJ.SG

- a

- naka."

- naka

- god

- god.

- "Dal

- dal

- but

- But

- ∅

- COP

- is

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- maldo

- maldo

- person

- person

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- that

- waitsau

- waitsau

- now

- now

- ob

- ob

- on

- on

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- the

- ospàk

- ospàk

- throne

- throne

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- mebwe

- mebwe

- father

- father

- âka

- âk-a-∅

- POSS-3-SUBJ.SG

- of him

- mpe,

- mpe-∅

- sit-NPST.SG

- sits,

- ndong

- ndo-ng

- INDEF(REF)-OBJ.SG

- a

- dempi."

- dempi

- child

- child.

- Sola

- sola

- when

- When

- i,

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I,

- ngu

- ngu

- as

- as

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- merkàt

- merkàt

- brother

- brother

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- Tol

- tol

- sun

- Sun

- on

- on

- and

- and

- Imbi,

- imbi

- moon

- Moon,

- ob

- ob

- on

- on

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- the

- ospàk

- ospàk

- throne

- throne

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- mebwe

- mebwe

- father

- father

- âki

- âk-i-∅

- POSS-1-SUBJ.SG

- of me

- mpen,

- mpe-n

- sit-PST.PFV.SG

- sat,

- isla

- isla

- towards

- before

- ta

- ta

- DYNAMIC

- even

- nonan

- non-n

- go-PST.PFV.SG

- went

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- isla

- isla

- towards

- to

- lunti

- lu-nti

- DEF-DAT.PL

- the

- lats

- lats

- country

- lands

- sai

- sai

- foreign

- foreign

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- that

- as

- ∅-s

- COP-PST.IPFV.PL

- were

- selkon

- selkon

- hostile

- hostile

- isla

- isla

- towards

- towards

- im,

- i-m

- 1-DAT

- me,

- nonan

- non-n

- go-PST.PFV.SG

- went

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- isla

- isla

- towards

- to

- lunti

- lu-nti

- DEF-DAT.PL

- the

- bwaikti

- bwaikti

- feast

- feasts

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- Ombàsi.

- Ombàsi

- Ombàsi

- the Mother Goddess.

- Bwenggorna

- bwenggor-n

- honor-PST.PFV.SG

- Honored

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- as

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

- them

- on

- on

- and

- and

- sâpabman

- sâpabm-n

- lift-PST.PFV.SG

- lifted

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- lung

- lu-ng

- DEF-OBJ.SG

- the

- ton

- ton

- hand

- hand

- âkî

- âk-i-ng

- POSS-1-OBJ.SG

- of me

- isla

- isla

- towards

- towards

- lum

- lu-m

- DEF-DAT.SG

- the

- omo

- omo

- mother

- mother

- eptàg.

- eptàg-∅

- shine-PTCP

- shining.

- Mbin

- mbi-n

- say-PST.PFV.SG

- Said

- tsip

- tsip

- thus

- thus

- i:

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I:

- "Dasi

- dasi

- goddess

- Goddess

- âki,

- âk-i-∅

- POSS-1-SUBJ.SG

- of me,

- ngu

- ngu

- as

- as

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- tol

- tol

- light

- light

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- the

- bwai!"

- bwai

- star

- stars!

- "Tsurtorbe

- tsurtor-be

- insult-PST.PFV.PL

- Have belittled

- luk

- lu-k

- DEF-SUBJ.PL

- the

- lats

- lats

- country

- lands

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- that

- an

- ∅-n

- COP-NPST.PL

- are

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- the

- wimès

- wimès

- neighbor

- neighbors

- âkis

- âk-i-s

- POSS-1-OBJ.PL

- of us

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- that

- papaube

- papau-be

- name-PST.PFV.PL

- named

- î

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- me

- 'aum

- au-m

- INDEF(OBL)-DAT.SG

- 'a

- dempi'

- dempi

- child

- child'

- î."

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- me.

- "Tsitsau,

- tsitsau

- then

- Then,

- paston

- pasto-n

- attack-NPST.PL

- are attacking

- ta

- ta

- DYNAMIC

- even

- ak

- a-k

- 3-SUBJ.PL

- they

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- the

- kak

- kak

- border

- borders

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- lats

- lats

- country

- land

- dautin

- dautin

- holy

- holy

- âklaingko,

- âk-laingko-∅

- POSS-2.HON-SUBJ.SG

- of you,

- dasi

- dasi

- goddess

- Goddess

- âki!"

- âk-i-∅

- POSS-1-SUBJ.SG

- of me!

- "Esompìs

- e-sompìs-∅

- IMPER-defeat-NPST.SG

- Conquer

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- the

- mpurnim!"

- mpurnim

- heathen

- heathens!

- Ranton

- ranto-n

- hear-PST.PFV.SG

- Heard

- Ombàsi

- Ombàsi

- Ombàsi

- the Mother Goddess

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- the

- lewai

- lewai

- word

- words

- âk

- âk

- POSS

- of

- lu

- lu-∅

- DEF-SUBJ.SG

- the

- mabm

- mabm

- mouth

- mouth

- âki.

- âk-i-∅

- POSS-1-SUBJ.SG

- of me.

- Ulan

- ula-n

- rise-PST.PFV.SG

- Raised

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- she

- im

- i-m

- 1-DAT

- me

- on

- on

- and

- and

- tsampin

- tsampi-n

- give-PST.PFV.SG

- gave

- a

- a-∅

- 3-SUBJ.SG

- she

- lum

- lu-m

- DEF-DAT.SG

- the

- itwam

- itwam

- arm

- arm

- âkim

- âk-i-m

- POSS-1-DAT

- of me

- lus

- lu-s

- DEF-OBJ.PL

- the

- bambor.

- bambor

- strength

- strength.

- Rambe

- rambe

- during

- Within

- rong

- ro-ng

- ten-OBJ.SG

- ten

- laid,

- laid

- year

- years,

- sompìsna

- sompìs-n

- defeat-PST.PFV.SG

- defeated

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- tsis

- tsi-s

- DEM3-OBJ.PL

- those

- roma

- roma-∅

- REL-SUBJ

- that

- mâukowa

- mâuk-owa

- protest-PLUP.PL

- had protested

- î.

- i-ng

- 1-OBJ.SG

- me.

- Ebrin

- ebri-n

- destroy-PST.PFV.PL

- Destroyed

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- as.

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

- them.

- Esulna

- esul-n

- take-PST.PFV.SG

- Took

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- aus

- au-s

- INDEF(OBL)-OBJ.PL

- ngaktìs,

- ngaktìs

- slave

- slaves,

- baus,

- baus

- ox

- oxen,

- on

- on

- and

- and

- gaibra,

- gaibra

- sheep

- sheep,

- on

- on

- and

- and

- pilain

- pilai-n

- send-PST.PFV.SG

- sent

- i

- i-∅

- 1-SUBJ.SG

- I

- as

- a-s

- 3-OBJ.PL

- them

- isla

- isla

- towards

- to

- lum

- lu-m

- DEF-DAT.SG

- the

- lats

- lats

- country

- land

- um

- um

- PART

- of

- Kasadgad.

- Kasadgad

- Kasadgad

- Kasadgad.

Translation

Thus speaks Tsinakan, the great king, king of the land of Kasadgad, brother to the sun and moon:

Before I sat on the throne of my father, all the foreign countries were hostile against me. The neighboring foreign countries spoke thus: "His father was a valiant king. He had conquered many enemy countries. Then he became a god. But the one who now sits on the throne of his father is a child."

When I, brother to the sun and moon, sat on the throne of my father, even before I went to the foreign countries who were hostile against me, I went to the feasts of the Mother Goddess. I celebrated them and I lifted my hand towards the shining mother. I spoke thus:

"O my mistress, light of the stars! The neighboring countries who called me 'a child' have belittled me. Then, they even started to attack the borders of your holy land, my mistress! Strike the heathen down!"

The mother goddess heard the words of my mouth. She rose me up and strengthened my arm. In ten years, I defeated those who had risen against me. I destroyed them. I captured prisoners, oxes and sheep, and I sent them back to the land of Kasadgad.