Eetafira

| Eetafira | |

| Period | c. 500 YP |

| Spoken in | Southeastern Coast of Tuysáfa |

| Total speakers | c. 200 thousand |

| Writing system | none |

| Classification | Dumic languages |

| Typology | |

| Basic word order | SOV |

| Morphology | analytical/agglutinative |

| Alignment | ERG-ABS |

| Credits | |

| Created by | Moose-tache |

Introduction

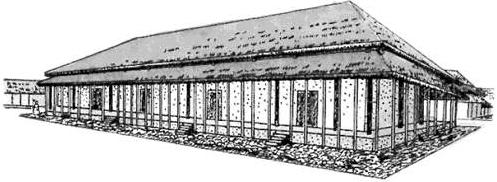

Eetafira is a Dumic language spoken by the Tendo ethnic groupd, on and near the southern coast of eastern Tuysáfa. It uses a topic-comment alignment with an underlying ergative-absolutive structure, and follows mostly SOV word order. Morphology on nouns is minimal, but the verbal complex has several layers of agglutination. Like its predecessor Potonsuti, Eetafira is relatively conservative. However, the language has absorbed a large body of loans from the east, since places like Jouki, Hazāka, and especially the Anatolionesian archipelago are the source of many social and technological innovations.

While many Tendo live in remote hill country in autonomous villages or tiny chiefdoms of a few hundred individuals, the core of the Eetafira speaking area is organized into polities that could be called advanced chiefdoms or primitive states. These kingdoms have nascent bureaucracy and extraction, official belief systems, mechanisms for power transfer, and career soldiers. In addition to an aristocratic class, there are now royal lineages that vie with the aristocrats for power. However, the Tenda lack writing, official currency, or a judiciary. These statelets have not wrested unquestioned authority from small scale authority structures, so land rights and usufructory rights are often a source of internal conflict. This is very different from the situation a few centuries before. The first half of the first millennium saw rapid change along the southern coast. Rice and ferric metallurgy arrived by 100 YP, after which there was a rapid expansion of both overall population and political complexity. By 500 YP some settlements are on the verge of creating urban market economies. Non food producing commoners are numerous as artisans, workers, and soldiers. But religious and political activity are still monopolized by the nobility.

Changes From Potonsuti

- Loss of ɰ (including j) and ɦ, creating vowel-initial words and vowel hiatus.

- Loss of final i and ʉ in words of more than one syllable.

- This change is blocked after a consonant cluster or β.

- Vowel hiatus yields long monophthongs.

- The sequence aa becomes long a.

- The sequences ii and ʉi become long i.

- The sequences ʉʉ and iʉ become long ʉ.

- The sequences ia, ɛa, and all remaining sequences ending in i or ɛ become long ɛ.

- The sequences ʉa, oa, and all remaining sequences ending in ʉ or o become long o.

- Short o becomes ʉ before a coda obstruent.

- All long vowels shorten before codas.

- Consonantal allophony

- P and k become ɸ and h, respectively, between vowels.

- Onstruents voice when immediately following a voiced consonant.

- These changes are productive and predictable. However, some of the phones produced are very marginally phonemic, since some speakers will use them in recent loan words.

Stem Alternations

Some verbs have separate but related stem forms in the perfective and imperfective.

Phonology

Onsets

| labial | dental | alveolar | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| obstruents | p | t | s | k | |

| nasals | m | n | |||

| approximants | β | ɾ/l |

ɾ and β are written r and v, respectively. Coda ɾ is realized and written l. The allophone ɸ is written f. Other allophones of the obstruents (h, b, d, z, g) are written as pronounced, although they are generally not phonemic or only marginally phonemic.

Vowels

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i · iː | ʉ · ʉː | |

| mid-high | o · oː | ||

| mid-low | ɛ · ɛː | ||

| low | a · aː |

ʉ and ɛ are written u and e, respectively. Long vowels are indicated by doubling the vowel.

Syllable Structure

Eetafira syllables follow the formula (C(C))V(ː)/(N/L(C)). Syllables may begin with any single consonant or vowel, as well as clusters of obstruents on rare occasion. The nucleus must have just one vowel. That vowel may be long in open syllables, or after a short vowel there may be a coda consonant, optionally preceded by a nasal or r. Nasal-nasal sequences only occur across syllable boundaries, and in fact any kind of double coda is rare. Coda nasals can be n or m word-finally, but match the place of articulation of any following consonant. If a vowel-initial suffix is attached to a coda consonant, the consonant is reanalyzed as an onset.

Because of a voiced/voiceless distinction in Proto-Dumic, some suffixes take different forms based on the shape of the preceding morpheme. V and r become b and z, respectively, after a coda (which due to phonological history will almost always be n/m or l). Similarly, some suffixes may consist of a long vowel that alternates with gV. These alternations show up in some compound words as well.

Words to demonstrate legal syllables:

tpaa “horse”

ee “pray”

Suprasegmental Features

Stress is not phonemic, and words have no pattern of stress aside from that imposed by the contours of prosody (although an entire word may be stressed to emphasize it). Pitch and volume both reduce slightly over the course of a prosodic unit until it is reset, usually at the boundary of a phrase or clause, after non-restrictive adjectives, and other situations.

Morpho-Syntax

Verbs

Verbs are the core of the Eetafira clause, and can form a complete sentence by themselves. They always come at the end of a clause, excluding conjunctions, which may follow a verb. They inflect for aspect, mood, valency, and tense with suffixes, but do not inflect for person or number agreement. The perfective aspect is used for completed (or to be completed) actions, while imperfective is used for everything else. Most verbs have an inherent lexical aspect that complicates grammatical aspect. For example, some verbs inherently have no duration and cannot properly be imperfective. However, these verbs may be used with the imperfective ending to indicate a perfect or habitual aspect. The imperative mood is used for commands. The irrealis mood is used for hypotheticals, giving second hand information cautiously, and other situations in which the speaker is not confident that the action being described is real. It is also used as a sort of potential future tense. The indicative mood is used for all other situations.

The transitive valency is used when there is an agent and a patient in the clause, although either or both may be omitted. These are marked with the ergative and absolutive cases, respectively. The ergative and absolutive are used in a syntactically consistent way even for verbs which have an experiencer instead of an agent, or a location instead of a patient, or other non-standard theta roles. When only one core noun phrase is present, i.e. a subject, it is always in the absolutive, and therefore will be parsed as a patient if it appears alone with a transitive verb. To indicate that it is the subject of an intransitive verb, the intransitive valency is used with a single absolutive subject. Although any noun phrases may be omitted, it is not grammatical to include an ergative noun phrase but not an absolutive. If only one noun phrase is present in the ergative/absolutive case, it is always parsed as absolutive. Therefore, if a speaker wishes to include an agent but omit a patient, a pronoun must be used to stand in for the absolutive.

Some verbs are treated inherently as intransitive verbs, with no need for a suffix. These verbs may also be treated as transitive without any formal change. The future suffix indicates future intent only. It is exclusive with the imperative and irrealis moods, and so mood and tense can be seen as one complex.

The role of the absolutive is lexically determined. In most cases, it is the experiencer of an intransitive verb, or the patient of a transitive verb. But its exact use can vary. One complicating factor is prefixes va-, ra-, and e-. The absolutive of verbs beginning with va- are usually locations, directions, or subjects of conversation. For verbs beginning with ra- they are usually beneficiaries or motivating reasons. And for e-, the absolutive is usually an instrument or method. These prefixes are not productive, and are presented here as a matter of etymology.

Clauses are negated by using ton before the verb.

| transitive | intransitive | |

|---|---|---|

| imperfective, indicative | ata | |

| imperfective, imperative | hen | ata |

| imperfective, irrealis | l | reeta |

| imperfective, future | hok | atahok |

| perfective, indicative | va | vaata |

| perfective, imperative | vahen | vaata |

| perfective, irrealis | val | vareeta |

| perfective, future | vahok | vaatahok |

Many verb stems end in a consonant other than n or l. Before any suffix that begins with r, p or h, or between three consonant clusters, the lost final i or u of the root is restored. This is a minefield of mistakes and overcorrection for Eetafira speakers. Most commonly, roots that used to end in i are frequently given u as a linking vowel instead. Some roots end in n or l in isolation also take a restored vowel before suffixes, and this is determined on a lexical basis.

The suffixes beginning with v become f in some cases after e, u, and a. These cases must be memorized, and this is another area that is rife with errors and innovations among native speakers. The suffixes -hen and -hok become -gen and -gok respectively after a voiced coda; the same alternation exists for the relative suffix -k/-gi. The combination of -hok/-gok and the relative suffix -k/-gi is -hohik/-gohik. Suffixes beginning in r similarly alternate with z after voiced codas.

Examples

| Teva engu |

| bed jump |

| He jumped (up and down) on the bed. |

| Teva engufa |

| bed jump-perfective |

| He jumped (up) on(to) the bed. |

| Teva engoota |

| bed jump-intransitive |

| The bed was jumping! |

| Teva ton enguhen |

| bed negative jump-imperative |

| don't jump on the bed! |

| Teva engufal |

| bed jump-perfective-irrealis |

| Suppose he jumped on the bed. |

| Kalzeeta |

| destroy-irrealis-intransitive |

| It may fail. |

Some verbs have perfective stems with a consonant cluster that does not exist in the imperfective stem.

| "Katahen" ktava |

| talk-imperative say-perfective |

| "Talk," he said. |

| Mivo kofa nahatal, pon tiha naktaval |

| wind tree wear.down-irrealis conjunction stick break-perfective-irrealis |

| Wind will wear down a tree, but break a stick. |

| Mahatak poopoo maktava |

| loud-relative boom make.a.noise-perfective |

| They made a loud boom. |

This is unrelated to the much more regular change of final i to e before the perfective ending.

| Eetafira sat, sateva |

| Eetafira speak speak-perfective |

| Speaking Eetafira, they spoke (the word). |

Verbs can also act as adjectives, in which case the verb precedes the target noun followed by -k/-gi. This is grammatically identical to a relative clause (see below).

| Kofa kee |

| tree yellow |

| The tree is yellow. |

| Kek kofa |

| yellow tree |

| The yellow tree. |

Verbs can also act as postpositions without any marking. This is grammatically identical to an adverbial clause (see below).

| Pik usa |

| bun enjoy |

| He enjoys some buns. |

| Pik usa ... |

| bun enjoy |

| Enjoying some buns(, he ...). |

In addition to compounding, which is common and highly productive in Eetafira, there are derivational suffixes that go between the root and the grammatical suffixes mentioned above. There are two argument-adjusting suffixes, or possibly valency-altering suffixes, that deserve special note. The first is -ho/-go, which indicates that the ergative is a cause rather than an agent. This also allows ergatives to appear with otherwise intransitive verbs.

| Ti tpaa sen. |

| 1sg horse see |

| I see the horse, or the horse is seen by me. |

| Ti tpaa seniho. |

| 1sg horse see-causative |

| I show the horse, or the horse is seen because of me. |

| Tpaa seta. Ti tpaa setaho. |

| horse happy. 1sg horse happy-causative |

| The horse is happy. I cheered up the horse, or the horse is happy because of me. |

The second is -ma, which indicates that the absolutive itself is also an agent. In other words, -ma is a reflexive suffix. Some other common deverbal suffixes include:

Verb > Noun

- -a : "-er" (intransitive subject or transitive patient)

- -ira : "-er," “the one who...” (transitive agent)

- -hen/-gen : instrument

- -fa/-ba : location

- -neta : result

- -noo : reason, goal

Verb > Verb

- -tim : inceptive

- -mumbi : cessative

- -sa : intensive, habitual

- -a : various uses, must be memorized

- -ru : resulting state

Examples

| Eea eetim |

| sing-subject sing-begin |

| The singer began to sing. |

| Ratanooe vatama kahesahen |

| go-goal run-intensive-imperative |

| Rocket toward your destination! |

Another thing which may complicate derivation is the fact that inherently verbal roots may become inherently nominal, and vice versa. This process is not productive, but several cases exist where a root may take verbal suffixes even though it is canonically a noun, and vice versa.

There is no copula in the present tense. Nouns which are equated are simply juxtaposed. However, when modal distinctions need to be indicated, the copula ii is used. It does not have a perfective version.

| Tpaa taa il... |

| horse here copula-irrealis |

| Assuming the horse is here... |

Nouns

Nouns are mostly uninflected, with the exception of derivational morphology and optional plural suffixes. Case is unmarked, including the ergative/absolutive distinction. Two case endings, genitive and dative, survive on pronouns (see below).

Living things are pluralized with -mo, and body parts are pluralized with -ta. All other nouns may be pluralized with -mo, but this rarely happens unless the plurality is being strongly emphasized.

Pronouns retain much more morphology than nouns, with both case suffixes and a greater number distinction, declining for singular, dual, and plural. Genitive pronouns are used for alienable possession, and possessive prefixes (listed below) are used for inalienable possession. These prefixes are usually option, but are almost always present for kinship terms and body parts.

| 1st, incl | 1st, excl | 2nd | 3rd | demonstrative | interrogative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | ti | ti | ma | tun | si | ra |

| dual | tita | kota | mata | tunda | sita | rata |

| plural | timo | komo | mamo | tummo | simo | ramo |

Genitive pronouns change the final vowel to ee, except tun which has a special genitive form tune.

Dative pronouns take a final ra, which becomes za in the form tunza.

The demonstrative pronoun/prefix is used whenever the gender of a noun is not known or considered unimportant, or for unpossessed things, and has no inherent implied distance. The interrogative pronoun/prefix is used when missing information is being sought by the listener.

Postpositions form a small, closed class of words. They can follow a noun, or be used with a possessive prefix.

- vatama : toward, before, until

- vatal : away from, after, since

- omima : into, through

- omil : out of, through

- vahe : under, about

- rafonda : near, alongside, with (commitative), in addition to

| Ravahe? |

| interrogative-about? |

| What is it about? |

The copula ii often functions as an adverb, and can serve a role similar to a postposition.

| Kop kiha ii kutava. |

| eight day copula die-perfective |

| He died on the eighth day. |

As with verbs, compounding is a very common, productive form of derivation for nouns. In addition, there are derivational suffixes that go between the root and any grammatical suffixes. A brief list follows.

Noun > Noun

- -fin/-bin : something related to X

- -vo/-bo : augmentative, honorific

Noun > Verb

- -hati/-gati : to make X

- -mil : to be X

- -o : to have X, X exists; this usually results in changing the final vowel to oo.

Alignment

Eetafira uses a topic-comment and ergative-absolutive alignment system. Core arguments of the verb are unmarked for tense. The one that most closely precedes the verb is the absolutive. Topics appear first among core arguments when they are introduced, but usually omitted after that. This results in a number of possible syntactic patterns.

First, transitive verbs with a stated ergative topic are very straightforward, with the ergative followed unceremoniously by the absolutive. Established topics are usually omitted, which is easy to do with ergative topics.

| Sonza tife nunnava. Mofa nunnava. |

| eagle mouse eat-perfective. all eat-perfective. |

| It was the eagle that ate the mouse. It ate everything. |

If the absolutive is the topic, it moves to the front, but a resumptive pronoun still appears before the verb. The fronted topic may be omitted, but not the resumptive pronoun. The ergative is usually not omitted when it is not the topic.

| Tee vombo ma tun kavava. Ma tun safiihok? |

| 1sg-genitive house 2sg 3sg destroy-perfective. 2sg 3sg fix-future? |

| It was my house you destroyed. Will you replace it? |

Intransitive verbs only take absolutive arguments, but topic fronting may still occur.

| Mahaton tun oho. |

| 2sg-leader 3sg beautiful. |

| Your head of household, he is beautiful. |

When the topic is possessive or dative, there is often no overt indication of this relationship.

| Pat vombo kasa. (as opposed to the equally grammatical pat tumbombo kasa.) |

| pig house big. |

| The pig’s house is big. |

| Ti ma kova see. (as opposed to the equally grammatical tira ma kova see.) |

| 1sg 2sg melon give. |

| You give me melons. |

Conjunctions

Conjunctions serve to connect phrases or clauses. There are two nominal conjunctions, vu (and) and pi (or). Verbal conjunctions are a little more complicated. They always come at the very end of the clause they modify, and form natural pairs, like because/therefore. Both of these can be used in the same sentence grammatically, but it is not necessary to use both.

- vuna : since, because (often used alone at the end of a sentence to add emphasis)

- tal : so, therefore

- rop : although, despite (often used alone at the end of a sentence to soften it)

- pon : but, however (often used alone at the end of a sentence to indicate unexpectedness)

- mumma : and, and then

When used with irrealis verbs, vuna is equivalent to "if."

Examples

| Sovu ratafa vuna sinoo tal. |

| bank go-perfective because lice-exist therefore. |

| Because we went to the river bank, I have lice. |

| Kuta rop. |

| die although. |

| She's dying (but...). |

| Ti seevaatahok, raamal vuna. |

| 1sg give-perfective-intransitive-future, benefactive-do-reflexive because |

| I will give up completely, if we help each other. |

Nested Clauses

Relative clauses are formed by adding -k/-gi to the main verb of the relative clause, after all other suffixes have been added. The relative clause precedes the noun phrase it modifies. The noun being modified also has a theta role in the relative clause, but it is usually omitted (this is the same as English: the word "dog" in "Susan likes the dog" is omitted when it becomes a relative clause: "That's the dog that Susan likes"). In some cases, especially if the modified noun plays a non-core role in the relative clause, the demonstrative pronoun si can be used.

Adverbial clauses are completely unmarked. They are placed at any point in a sentence before the verb they modify. A related category is subordinate clauses, in which a clause takes the role of a noun phrase within a larger clause. These are formed by taking an adverbial clause (i.e. an unmarked clause) and adding the word kata. This noun acts just like any other, including taking case and number markings. Kata is especially common before verbs of speech and psychic action, but can appear in any context.

Examples

| Vii afek aldovira |

| water drink-relative crow |

| The crow that drinks water ("crow" is omitted from the relative clause). |

| Sira run masa sek aldovira |

| demonstrative-dative man food give-relative crow |

| The crow that the man gave food to ("crow" goes with the dative pronoun in the relative clause). |

| Toto pak tut |

| bad bow use. |

| He uses a bow badly. -or- Using a bow badly(, he...). |

| Kifon nunna kata itahava |

| dirt eat subordinate make-perfective. |

| He made him eat dirt (kata, and therefore the whole subordinate clause, fills the absolutive role). |

Questions and Exclamations

Yes/no questions are formed by adding a rising intonation to the end of a sentence, possibly with a prompt like tohoo? ("right?"). They may be answered in the affirmative with simil, and the negative with kim.

More substantive questions are formed by replacing the missing information with ra. This may function as a standalone word, or a possessive/demonstrative prefix.

Examples

| Moho nunna tohoo? |

| fruit eat right? |

| Are you eating fruit? |

| Rasolza moho nunna? |

| interrogative-when fruit eat? |

| When are you eating fruit? (note the obsolete dative suffix on what is now just an adverb) |

| Ma ra? |

| 2sg interrogative? |

| Who are you? |

Exclamatory statements may be emphasized by adding vuna (see above). Vocative exclamations may be formed by adding oo to the beginning.

| Oo katombo, kutava vuna? |

| vocative leader-honorific die-perfective because |

| Father, have you really died? |

Numbers

1 : ana

2 : mik

3 : pira

4 : ata

5 : pii

6 : sima

7 : tato

8 : kop

9 : nundi

10 : kaa

11 : kaa vu ana

20 : mihihaa

100 : tik

Numbers do not fit into any existing part of speech. Ordinal numbers precede the noun they modify (after any relative clauses/adjectives), while cardinal numbers follow it, but still come before postpositions. In both cases, numbers are entirely unmarked. The words poso ("several"), mal ("few"), and kefe ("none") behave the same way as numbers, grammatically.

| tifemo tato |

| Seven mice. |

| tato tife |

| The seventh mouse. |

| tifemo poso vahe |

| Concerning many mice. |

Lexicon

The Eetafira lexicon can be found here: Eetafira/lexicon

Sample Text

The Chief and the Mouse

| Mosok katon ton membok vombo omima tondava, mumma imiruneta ehutaval tal uhosava. |

| A famous chief was put in a house with no openings, and abandoned so that he might die of starvation. |

| Veta kponda moo, katon ek tife vombo omil kahe kata sen. |

| Sitting gloomily on the ground, the chief saw a little mouse running around the house. |

| A “sitife nunna vuna ton imil” kata sat, tune taha mini. |

| “I will eat this mouse to keep from starving” said the chief, as he seized his knife. |

| Simil rop, a “rara tife konzeval vuna is ti kutaval” kata sat, katon taha safeva. |

| But then, saying “Even if I kill the mouse, I will still die,” he put away his knife. |

| Talda tife “oo sungok katombo, ti niteva vuna ma niteva” kata sateva. |

| Surpsingly, the mouse said “Great chief! Because you have spared me, I will spare you.” |

| Tife ek memba omima ratafa mumma masa vu moho minik tifemo mihihaa pirahaa rafonda kemba. |

| The mouse went into a small hole, and came back with twenty or thirty mice, carrying grains and fruit. |

| Kiha pii omima masa see, mumma sima kiha sofan vombo reefa. |

| They fed him for five days, and on the sixth day the chief's captors opened the hut. |

| Katon pase koral vuna talda tal. |

| They were astonished that the chief was alive and healthy. |

| Sihatombo sungok sutoo! Ton nunna, ton afe, rop kora tek kee!” kata sateva. |

| “This chief has a powerful will! He can live without eating or drinking!” they said. |

The North Wind and the Sun

| Poomivo vu mira ra kira sungoo sen sirel mumma esik ovi tonzak naveera kemba. |

| The north wind and the sun were arguing over which one was stronger, when a traveler came by wearing a thick cloak. |

| Naveera ovi vahava kata itaheera kira sungoo kata kombava. |

| They agreed that whoever first made the traveler take off their coat would be the stronger one. |

| Poomivo sita arun poo pon noo ovi kira onap naveera tonzama. |

| The north wind blew as hard as it could, but the traveler just wrapped the cloak around themselves tighter. |

| Mumma mira rutamil. |

| Then it was the sun’s turn. |

| Nun nee mumma naveera ovi vahava. |

| It shined warmly, and the traveler took off the cloak. |

| Poomivo mira kira sungoo kata kombava. |

| The north wind agreed that the sun was stronger. |