Potonsuti

| Potonsuti | |

| Period | c. 0 YP |

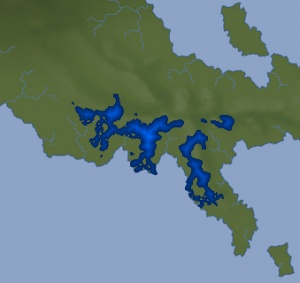

| Spoken in | Southeastern Coast of Tuysáfa |

| Total speakers | c. 60 thousand |

| Writing system | none |

| Classification | Dumic languages |

| Typology | |

| Basic word order | SOV |

| Morphology | analytical/agglutinative |

| Alignment | ERG-ABS |

| Credits | |

| Created by | brandrinn |

Introduction

Potonsuti is a Dumic language spoken near the southern coast of eastern Tuysáfa. It is mostly spoken in the hills and mountain valleys above the coast, and only in some places are Potonsuti speakers the majority on the shore itself. This is the origin of the name, meaning "mountain language." The people's name for themselves is Tento. They are scattered in small villages loosely organized into dozens of chiefdoms. They have no knowledge of writing, ferric metallurgy, market economies, standing armies, currency, or large scale urbanization. There is a limited form of social class, in that the chiefly families form an endogamous group separated from the rest of society by ritual importance and wealth. The chiefly caste is responsible for conducting large public religious rites and organizing public works projects, and extract a comfortable living from the farmers and the tiny group of specialized artisans.

Other Dumic languages include Wokatasuto, spoken on the Wohata coast, Trinesian, spoken on several offshore islands, and Kataputi, from the city states along the southeastern shore of the Great Bay.

Changes From Proto-Dumic

- Loss of unstressed vowels

- Immediately pre-stress vowels are lost between two non-identical voiceless consonants

The stem alternations this causes, so crucial in other Dumic languages, are mostly reversed by analogy (but see below for surviving examples).

- Reduction of R

- r → ɾ

- V₁ɾV₁ → V₁l (sporadically reversed across morpheme boundaries)

- V₁wV₁ → V₁l (sporadic, possibly the result of interdialectal borrowing)

- w ð ɣ ɾ → p t k s / l_ (but see below about the leveling of ð/t alternation)

- Reduction of N

- V → V[+nasal] / _N$

- n → ∅ / _$

- m → m~n~n̠~ŋ / _C, assimilates wrt the POA

- m → n / _#

- Vowel chain shift

- u → o

- ã ĩ ũ → ɑ ɛ ʉ

- Transformation of approximants

- ð → ɦ

- ɣ → ɰ

- ɰ → j / i_ (operates even across morpheme boundaries)

- w → β

- ɦ > β /ɦo_ (only within morphemes)

- ɰ > β /ɰo_ (only within morphemes)

At some point the relationship between ð and t was lost, so that the change from the former to the latter is no longer productive in suffixes and non-opaque compounds.

- Vowel merge

- ɑ → o / _N$

- ɑ → a

- Vowel lowering

- i → ɛ /_βa,_ja (operates even across morpheme boundaries)

Stem Alternations

The different forms created in nouns and verbs by vowel loss and then stress movement to the right due to suffixation are mostly leveled by analogy. There are four situations in which this change has not been reversed.

- First, for a small number of verbs, the vowel loss has created a separate perfective version of the stem, which is used before all suffixes in the perfective, and no suffixes in the imperfective. The vowel loss is on the second to last syllable of the root. See the verb section for examples.

- Second, some adverbs are formed by adding -ri, -ken, or -ta to nouns with vowel loss on the second to last syllable of the noun. For example, kpanta "on the ground, at ground level."

- Third, some opaque compounds have vowel loss on the last syllable of the first element of the compound. For example, senkteβa "winter bed."

- Fourth, a small number of trisyllabic states and nouns have been reanalyzed as bisyllabic after a permanent vowel loss in either the first or second syllable. For example, tkihi "sharp" and tpaha "horse."

Phonology

Onsets

| labial | dental | alveolar | velar | glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| voiceless | p | t | s | k | |

| voiced | β | ɾ/l | ɰ/j | ɦ | |

| nasals | m | n |

ɾ and ɦ are written r and h. After i, ɰ is realized as j, and is written j in this article. ɾ is realized as l in coda position (see below), and is written l in this article.

Vowels

| front | central | back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| high | i | ʉ | |

| mid-high | o | ||

| mid-low | ɛ | ||

| low | a |

Syllable Structure

All Potonsuti syllables must begin with a consonant and contain exactly one vowel. There are no diphthongs or initial vowels.

The only phonemic codas allowed are n and l. Intervocally, any consonant may follow n or l to form a cluster, although clusters ending in β, r, ɰ, or h are only possible across morpheme boundaries, for example in compound words. There are also initial clusters, which can combine any two non-identical voiceless consonants. Phonetically, the first element of an initial cluster may be pronounced as a coda if the previous syllable ends in a vowel, but for phonemic purposes only n and l are considered possible codas.

Suffixes beginning with β, r, or ɰ begin with p, s, or k instead after certain coda n or l, after the vowel u, and unpredictably after the vowels a or e. This also applies to the second element of many older, more opaque compound words.

Suprasegmental Features

Stress is not phonemic, and words have no pattern of stress aside from that imposed by the contours of prosody (although an entire word may be stressed to emphasize it). Pitch and volume both reduce slightly over the course of a prosodic unit until it is reset, usually at the boundary of a phrase or clause, after non-restrictive adjectives, and other situations.

Morpho-Syntax

Verbs

Verbs are the core of a Potonsuti clause, and can form a complete sentence by themselves. They always come at the end of a clause, excluding conjunctions, which may follow a verb. They inflect for aspect, mood, and valency with suffixes, but do not inflect for person, number, or tense. The perfective aspect is used for completed (or to be completed) actions, while imperfective is used for everything else. Most verbs have an inherent lexical aspect that complicates grammatical aspect. For example, some verbs inherently have no duration and cannot properly be imperfective. However, these verbs may be used with the imperfective ending to indicate a perfect or habitual aspect. The imperative mood is used for commands. The irrealis mood is used for hypotheticals, giving second hand information cautiously, and other situations in which the speaker is not confident that the action being described is real. The indicative mood is used for all other situations. The transitive valency is used when there is an agent and a patient in the clause, although either or both may be omitted. These are marked with the ergative and absolutive cases, respectively. The ergative and absolutive are used the same way even for verbs which have an experiencer instead of an agent, or a location instead of a patient, or other non-standard theta roles. When only one core noun phrase is present, i.e. a subject, it is always in the absolutive, and therefore will be parsed as a patient if it appears alone with a transitive verb. To indicate that it is the subject of an intransitive verb, the intransitive valency is used with a single absolutive subject. Although any noun phrases may be omitted, it is not grammatical to include an ergative noun phrase but not an absolutive. If only one noun phrase is present in the ergative/absolutive case, it is always parsed as absolutive. Therefore, if a speaker wishes to include an agent but omit a patient, a pronoun must be used to stand in for the absolutive. Some verbs are treated inherently as intransitive verbs, with no need for a suffix. These verbs may also be treated as transitive without any formal change. Clauses are negated by using ton before the verb.

| transitive | intransitive | |

|---|---|---|

| imperfective, indicative | hata | |

| imperfective, imperative | ken | hata |

| imperfective, irrealis | ri | rihata |

| perfective, indicative | βa | βahata |

| perfective, imperative | βaken | βahata |

| perfective, irrealis | βari | βarihata |

Examples

| teβa ɰenku |

| [bed] [jump] |

| He jumped (up and down) on the bed. |

| teβa ɰenkupa |

| [bed] [jump][perfective] |

| He jumped (up) on(to) the bed. |

| teβa ɰenkuhata |

| [bed] [jump][intransitive] |

| The bed was jumping! |

| teβa ton ɰenkuken |

| [bed] [negative] [jump][imperative] |

| don't jump on the bed! |

| teβa ɰenkupaii |

| [bed] [jump][perfective][irrealis] |

| Suppose he jumped on the bed. |

Some verbs have perfective stems with a consonant cluster that does not exist in the imperfective stem.

| "kataken" ktaβa |

| [talk][imperative] [say][perfective] |

| "Talk," he said. |

| miβo kopa nakatari, pon tika naktaβari |

| [wind] [tree] [wear down][irrealis] [conj] [stick] [break][perfective][irrealis] |

| Wind will wear down a tree, but break a stick. |

| makataki poho-poho maktaβa |

| [loud][subord] [boom boom] [make a noise][perfective] |

| They made a loud boom. |

This is unrelated to the much more regular change of final i to e before the perfective ending.

| potonsuti sati, sateβa |

| [Potonsuti] [speak] [speak][perfective] |

| Speaking Potonsuti, they spoke (the word). |

Verbs can also act as adjectives, in which case the verb precedes the target noun followed by ki. This is grammatically identical to a relative clause (see below).

| kopa kijo |

| [tree] [yellow] |

| The tree is yellow. |

| kijoki kopa |

| [yellow] [tree] |

| The yellow tree. |

Verbs can also act as postpositions without any marking. This is grammatically identical to an adverbial clause (see below).

| piki husa |

| [bread] [enjoy] |

| He enjoys some bread. |

| piki husa ... |

| [bread] [enjoy] |

| Enjoying some bread(, he ...). |

In addition to compounding, which is common and highly productive in Potonsuti, there are derivational suffixes that go between the root and the grammatical suffixes mentioned above. There are two argument-adjusting suffixes, or possibly valency-altering suffixes, that deserve special note. The first is -ko, which indicates that the ergative is a cause rather than an agent. This also allows ergatives to appear with otherwise intransitive verbs.

| Ti tpaha seni. |

| [1sg] [horse] [see] |

| I see the horse, or the horse is seen by me. |

| Ti tpaha seniko. |

| [1sg] [horse] [see][causative] |

| I show the horse, or the horse is seen because of me. |

| Tpaha seta. Ti tpaha setako. |

| [horse] [happy]. [1sg] [horse] [happy][causative] |

| The horse is happy. I cheered up the horse, or the horse is happy because of me. |

The second is -ma, which indicates that the absolutive itself is also an agent. In other words, -ma is a reflexive suffix.Some other common deverbal suffixes include:

Verb > Noun

- ha : "-er" (intransitive subject or transitive patient)

- hira : "-er" (transitive agent)

- ken : instrument

- pa : location

- neta : result

- noɰo : reason, goal

Verb > Verb

- timi : inceptive

- mumpi : cessative

- sa : intensive, habitual

- ha : various uses

- ru : resulting state

Examples

| ɰijeha ɰijetimi |

| [sing][subject] [sing][begin] |

| The singer began to sing. |

| ratanoɰohe βatama kakesaken |

| [go][goal] [run][intensive][imperative] |

| Rocket toward your destination! |

Another thing which may complicate derivation is the fact that inherently verbal roots may become inherently nominal, and vice versa. This process is not productive, but several cases exist where a root may take verbal suffixes even though it is canonically a noun, and vice versa.

There is no copula in the present tense. Nouns which are equated are simply juxtaposed. However, when aspectual or modal distinctions need to be indicated, the copula hi is used.

Nouns

Nouns inflect for number and case with suffixes. Absolutive/ergative is unmarked and used for the agent and patient of transitive sentences, and the subject of intransitive sentences. The genitive indicates possession or association, and is the object of postpositions. The dative indicates target, recipient, or beneficiary. The instrumental indicates means or other adverbial meanings. The locative indicates location. Absolutive and ergative are usually distinguished by word order, with the ergative coming early in the clause, and the absolutive coming immediately before the verb. This can be subverted by adding ha to the beginning of a clause, which indicates that the absolutive will appear before the ergative. If there is only one unmarked noun phrase in a clause, it is always absolutive. Plural is exactly what it sounds like, but body parts use a different plural marker: ta.

| abs/erg | genitive | dative | instrumental | locative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | he | ra | ken | ta | |

| plural | mo | mohe | mora | moken | mota |

Pronouns are grammatically no different from other nouns, with the exception that they decline for singular, dual, and plural. The pronouns take the same case endings as any other noun. They are also identical in form to the possessive prefixes. Alienable possession is indicated by pronouns in the genitive case. However, inalienable possession is indicated with possessive prefixes. They are normally optional, but they are mandatory for body parts and kinship terms.

| 1st, incl | 1st, excl | 2nd | 3rd, masc | 3rd, fem | demonstrative | interrogative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular | ti | ti | ma | ka | tun | si | ra |

| dual | tita | kota | mata | kata | tunta | sita | rata |

| plural | timo | komo | mamo | kamo | tummo | simo | ramo |

The demonstrative pronoun/prefix is used whenever the gender of a noun is not known or considered unimportant, or for unpossessed things, and has no inherent implied distance. The interrogative pronoun/prefix is used when missing information is being sought by the listener.

Postpositions form a small, closed class of words that must follow the genitive form of a noun (or pronoun).

- βatama : toward, before, until

- βataɾi : away from, after, since

- homima : into, through

- homil : out of, through

- βake : under, about

- raponta : near, alongside, with (commitative), in addition to

As with verbs, compounding is a very common, productive form of derivation for nouns. In addition, there are derivational suffixes that go between the root and any grammatical suffixes. A brief list follows.

Noun > Noun

- pini : something related to X

- βo : augmentative, honorific

Noun > Verb

- kati : to make X

- mil : to be X

- ho : to have X, X exists

Conjunctions

Conjunctions serve to connect phrases or clauses. There are two nominal conjunctions, βu (and) and pi (or). Verbal conjunctions are a little more complicated. They always come at the very end of the clause they modify, and form natural pairs, like because/therefore. Both of these can be used in the same sentence grammatically, but it is not necessary to use both.

- βuna : since, because (often used alone at the end of a sentence to add emphasis)

- tal : so, therefore

- ropi : although, despite (often used alone at the end of a sentence to soften it)

- pon : but, however (often used alone at the end of a sentence to indicate unexpectedness)

- mumma : and, and then

When used with irrealis verbs, βuna is equivalent to "if."

Examples

| soβu ratapa βuna sinuho tal |

| [bank] [go][perfective] [because] [lice][exist] [therefore] |

| Because we went to the river bank, I have lice. |

| kuta ropi |

| [die] [although] |

| She's dying (but...). |

Nested Clauses

Relative clauses are formed by adding ki to the main verb of the relative clause, after all other suffixes have been added. The relative clause precedes the noun phrase it modifies. The noun being modified also has a theta role in the relative clause, but it is usually omitted (this is the same as English: the word "dog" in "Susan likes the dog" is omitted when it becomes a relative clause: "That's the dog that Susan likes"). In some cases, especially if the modified noun plays a non-core role in the relative clause, the demonstrative pronoun si can be used.

Adverbial clauses are completely unmarked. They are placed at any point in a sentence before the verb they modify. A related category is subordinate clauses, in which a clause takes the role of a noun phrase within a larger clause. These are formed by taking an adverbial clause (i.e. an unmarked clause) and adding the word kata. This noun acts just like any other, including taking case and number markings. Kata is especially common before verbs of speech and psychic action, but can appear in any context.

Examples

| βihi hapeki ɰaru |

| [water] [drink][relative] [crow] |

| The crow that drinks water ("crow" is omitted from the relative clause). |

| siɾa run masa soheki ɰaru |

| [demons][dative] [man] [food] [give][relative] [crow] |

| The crow that the man gave food to ("crow" goes with the dative pronoun in the relative clause). |

| toto paki tuti |

| [bad] [bow] [use] |

| He uses a bow badly. -or- Using a bow badly(, he...). |

| kipon nunna kata hitakaβa |

| [dirt] [eat] [subordinate] [make][perfective] |

| He made him eat dirt (kata, and therefore the whole subordinate clause, fills the absolutive role). |

Questions and Exclamations

Yes/no questions are formed by adding a rising intonation to the end of a sentence, possibly with a prompt like tokoɰo? ("right?"). They may be answered in the affirmative with simil, and the negative with kimi.

More substantive questions are formed by replacing the missing information with ra. This may function as a standalone word, or a possessive/demonstrative prefix.

Examples

| moko nunna tokoɰo? |

| [fruit] [eat] [right] |

| Are you eating fruit? |

| rasolsa moko nunna? |

| [what][time][dative] [fruit] [eat] |

| When are you eating fruit? |

Exclamatory statements may be emphasized by adding βuna (see above). Vocative exclamations may be formed by adding ho to the beginning.

Numbers

1 : kaha

2 : miki

3 : pira

4 : hata

5 : piji

6 : sima

7 : tato

8 : kopu

9 : nunti

10 : kaɰa

11 : kaɰa βu kaha

20 : mikikaɰa

100 : tiki

Numbers do not fit into any existing part of speech. Ordinal numbers precede the noun they modify (after any relative clauses/adjectives), while cardinal numbers follow it, but still come before postpositions. In both cases, numbers are entirely unmarked. The words poso ("several"), mal ("few"), and kepe ("none") behave the same way as numbers, grammatically.

Examples

| tipemo tato |

| Seven mice. |

| tato tipe |

| The seventh mouse. |

| tipemohe poso βake |

| Concerning many mice. |

Cultural Lexicon

All words are given without number, possession, aspect, or any other grammatical affixes, even if they would not appear in actual usage without them. Unless otherwise specified, the word in parentheses matches the English word in part of speech (with the adjectives being intransitive verbs).

There are five seasons: spring (mamu), early summer (mihu), late summer (ronton), autumn (rapi), and winter (senka). The early summer shares its name with the rains that make agriculture possible, while the late summer shares its name with the hurricane. The Tento revere both of these natural forces, and hope to gain the favor of both to reach a successful harvest (miniru). Other important features of nature are streams (soβu), stones (karo), the sun (mira), the sky (paɰa), and the Earth (kipon). There are several important domesticated animals, such as pigs (pati), cows (sosina), sheep (kapo), and dogs (toɰi). They, as well as popular game animals like deer (ɰomma) and rabbit (kakeha), provide meat, as well as eggs (toβa) and cheese (paton). Oxen and horses (tpaha) also provide transportation and traction. The primary staple is wheat (masa), which is cooked (nopa) to make bread (piki) and porridge (maka). Other plants and animals include fruit (moko), trees (kopa), grass (paro), flowers (some), insects (tenka), rodents (sako), birds (toβira), turtles (pimaro), and the ferocious lion (renpu). The mines yield salt (ɰini), as well as the metals needed to make bronze (ɰanaso) and gold (nijaha) objects.

The Tento worldview revolves around the binary distinction between the ordinary world (kaβi) and the spirit world (sopipa), which is also the home of ancestors (tunha) and gods (tipi). These two worlds may come into contact in certain people and places, resulting in individuals or locations with great magical power (sunka). Those with the greatest magical power are mystics (kiraβu) and chiefs (katon), though even they have limited control over how the spirit world affects the ordinary world. Once a person dies (kuta), they are given a burial designed to make them comfortable in the spirit world, so that they may bestow blessings upon their descendants, and the living (koraha) in general. Among common burial items are jewelry, cloth (poki), furniture, and tools. Time (sol) is divided into the past (tamo), present (nenti), and future (ɰisi) (note: these are verbs). Publicly, the whole community will participate in the planting and harvest sacrifices (nate) in the public circle (ɰol). Privately, there are personal prayers (suti) which can be said alone or in the presence of a mystic, especially to ward off illness (ɰil). Dead bodies, a person who has killed (konsi) someone, menstruating women, and other things having to do with death are thought to be ritually polluted (haka). The animals (katon) are also revered, as they often have an unseen connection to the spirit world.

The most important kin are the immediate family, especially the father (taha) and mother (monha), or less formally dad (tata) and mom (mommon). A person's older brothers (penka) and older sisters (nunti) have seniority within the household, while the younger brothers and sisters (himiha) are less senior. A young boy (motu) will live in his father's house after marriage, even as a grown man (run), though only the eldest son will inherent the bulk of his father's estate. A young girl (kil) will live in her father's house, until she is a marriageable woman (ronsa), gets married, and moves into her husband's house. The household shares its wealth, while most economic exchanges outside the household take place in the form of gift-giving (sohe), which creates countless reciprocal bonds of obligation throughout the village (mariro). Most people are farmers (minihira), though some are artisans and craftsmen (ɰatihira), not to mention idle elites. They live in houses (βompo) containing an average of about seven people per household (sihon). They use hoes (notoho) to work the fields (tapapa) and axes (kani) to clear the forests, sleep in hay-filled beds (teβa), eat (nunna) from low tables (pono) using their hands or a spoon, and drink (hape) water (βihi) or alcohol (mapa). For recreation they might sing (ɰije) or dance (pakon), but as always the most popular activity is to have sex with (husa) someone. They wear tunics (kome) tied with a belt (kasa), trousers (kara) over their legs (kasi), and leather shoes (moni). Important body parts include arms (βata), nose (toɰu), ear (mata), eye (βeti), and hands (poɰa). Everyone hates (nata) and shuns (kuno) the foolish man (hoβi) or the disgusting woman (suki), but they love (nenki) or admire (kasa) the courageous man (ɰopun) or the graceful woman (toβira).

People might go (ɾata), run (kake), jump (ɰenku), or swim (nenka) to get around, while animals might fly (sipe). Humans distinguish themselves by thinking (pil), speaking (sati) and changing their environment by making (ɰati) things happen. Visual perception is divided into two verbs, perception done by the perceiver (noho), and perception done by the perceived (seni), similar in meaning to “watch” and “see,” respectively (seni is also used to mean "about" or "regarding." Audio perception is also divided along these lines, perception by the perceiver (taso), and by the perceived (nompa), loosely matching “listen” and “hear.” Objects can be red (kihi), blue (kunsi), green (ɰeton), or yellow (kijo), as well as white (mahi) and black (toɰata). They can be big (kaha) or small (haɰi), thick (hesi) or thin (tako), round (ɰese) or flat (pihi), long (naka) or short (soɰi). They can be hot (meti) or cold (kisa), clean (mire), or dirty (βil). People can also be happy (seta) or depressed (kaɰana) or angry (raβa, or ral). They can be beautiful (hoko) or ugly (kato).

Sample Text

The Chief and the Mouse

| Mosoɰaki katon ton mempahoki βompohe homima tontaβa mumma ɰimirunetara kutaβari tal hukosaβa. |

| A famous chief was put in a house with no openings, and abandoned so that he might die of starvation. |

| βeta kponta maɰo katon haɰiki tipe βompohe homil kake kata seni. |

| Sitting gloomily on the ground, the chief saw a little mouse running around the house. |

| Ha “sitipe nunna βuna ton ɰimiru” kata katon sati kataka mini. |

| “I will eat this mouse to keep from starving” said the chief, as he seized his knife. |

| Simil ropi ha “rara tipe konseβa tal ɰisi ti kutaβaɾi βuna” kata sati katon taka sapeβa. |

| But then, saying “Even if I kill the mouse, I will still die,” he put away his knife. |

| Talta tipe “ho sunkahoki katonpo ti niteβa βuna ma niteβa” kata sateβa. |

| Surpsingly, the mouse said “Great chief! Because you have spared me, I will spare you.” |

| Tipe haɰiki mempahe homima ratapa mumma masa βu moko miniki tipemohe mikikaɰa pirakaɰa raponta kempa. |

| The mouse went into a small hole, and came back with twenty or thirty mice, carrying grains and fruit. |

| Kikahe piji homima masa sohe mumma sima kikata sopani βompo rahepa. |

| They fed him for five days, and on the sixth day the chief's captors opened the hut. |

| Katon pase koraru βuna talta tal. |

| They were astonished that the chief was alive and healthy. |

| Sikatonpo sunkahoki sutiho! ton nunna ton hape ropi kora teku kija!” kata sateβa. |

| “This chief has a powerful will! He can live without eating or drinking!” they said. |

The North Wind and the Sun

| Poɰahe miβo βu mira ra kira sunkaho seni sireru mumma hesi hoβi tonsaki naβahira kempa. |

| The north wind and the sun were arguing over which one was stronger, when a traveler came by wearing a thick cloak. |

| Naβahira hoβi βakaβa kata hitakaki ka kira sunkaho kata kompaβa. |

| They agreed that whoever first made the traveler take off their coat would be the stronger one. |

| Poɰahe miβo sita harun poho pon noɰo hoβi kira honapi naβahira tonsama. |

| The north wind blew as hard as it could, but the traveler just wrapped the cloak around themselves tighter. |

| Mumma mirahe rutamil. |

| Then it was the sun’s turn. |

| Nuni nija mumma naβahira hoβi βakaβa. |

| It shined warmly, and the traveler took off the cloak. |

| Poɰahe miβo mira kira sunkaho kata kompaβa. |

| The north wind agreed that the sun was stronger. |