Proto-Western/Grammar

| Written by Dewrad. |

Proto-Western is the parent language of the Western family. It was spoken roughly contemporaneously with Ngauro in the eastern areas of the Great Western Plain. While most of its descendants remain in the Great Western Plain, one branch has migrated eastwards into the Edastean sphere, giving rise to two languages, Gezoro and Tjakori.

Phonology

The reconstructed consonant phoneme inventory of Proto-Western is shown in the table below:

| bilabial | alveolar | pal-alv | palatal | velar | labiovelar | glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stops | voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ | ʔ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | kʷʰ | ||||

| voiced | b | d | ||||||

| affricates | voiceless | c | č | |||||

| aspirated | cʰ | čʰ | ||||||

| voiced | dz | dž | ||||||

| fricatives | voiceless | s | š | |||||

| voiced | γ | γʷ | ||||||

| laterals | approximant | l | ||||||

| fricative | ł | |||||||

| nasals | m | n | ñ | |||||

| approximants | w | y | ||||||

The vowel phonemes are shown in the table below:

| front | back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| close | oral | i | u |

| nasal | ĩ | ũ | |

| open | oral | e | a |

| nasal | ẽ | ã | |

Syllable and root structure

Obligatory segments of the Proto-Western syllable are the onset and rime. The onset can be any single consonant or a cluster consisting of a lateral, a nasal or an approximant preceded by an obstruent (a stop, an affricate or a fricative, excluding the glottal stop). The rime obligatorily consists of a nucleus, which may be any vowel, followed by an optional coda, which could be either any single consonant or a cluster made up of the glottal stop, any lateral or an approximant followed by an obstruent.

Restricting the preceding, it appears that clusters were impermissible in auslaut and that an inlaut syllable could not end in a coda cluster. Additionally, any cluster formed by a coda and an onset coming into contact in inlaut had to conform to the cluster rules given above. Another restriction appears to be that inflectible roots could not end in a checked syllable: all inflectible roots ended in a vowel. Vowels in hiatus were impermissible, and any hiatuses produced by inflection were broken by means of the glottal stop.

Allophony

As Proto-Western is a reconstructed language, it is probably impossible to discover detailed information about the language's allophonic processes. However, by examining reflexes in daughter languages, we can note a few salient processes:

- In pausa (i.e. before a phrase boundary), stops were unreleased. Additionally, labiovelar phonemes would lose their labial coarticulation in the same position, merging with the plain velars.

- Palato-alveolar obstruents do not occur before back vowels, nor do alveolar obstruents occur before front vowels. Morphophonemic processes demonstrate that alveolar stops and affricates become palato-alveolar affricates before front vowels, likewise *s becomes *š before front vowels. There are remnants of a similar alternation between *l and *y, which has led to scholars positing that the palato-alveolar series was originally palatal or palatalised.

Suprasegmentals

| i.e. those who wish to derive a language from PW can suit themselves. |

The accentual system of Proto-Western is as yet unknown. Gezoro and Tjakori seem to have exhibited a pitch-accent system, the Steppe languages have a strong stress accent while the Coastal languages tend to be tonal. Unfortunately, the data in the daughter languages are too conflicting for us to confidently reconstruct the Proto-Western system.

Prehistory of the Proto-Western sound system

| I just thought this might be interesting. |

By means of internal reconstruction, we can draw some tentative conclusions about the nature of Pre-Proto-Western's phonological system. It seems clear that the voiced (labio-)velar fricatives are reflexes of earlier voiced stops, due to the "gap" in the phoneme system. As mentioned earlier, the palato-alveolars appear to have originally been palatalised alveolars, with Proto-Western *y deriving from an earlier *lj. However, due to there being no traces of a similar alternation between *n and *ñ, some have concluded that the Proto-Western palatal nasal was originally velar, which again would render the inventory more balanced.

Morphology

Broadly, Proto-Western was only lightly inflecting, falling more towards the isolating end of the synthesis spectrum (although it was less isolating than, say, English).

Noun phrase constituents

Nominal morphology

Proto-Western nominals inflected for case, number and possessor. Lacking a separate class of adjectives, the derivational morphology of Proto-Western was remarkably rich, as derivational morphemes were used to refine and extend the meanings of nouns in a similar way to adjectives in orther languages.

A fundamental opposition in Proto-Western nominals was the distinction between edible and inedible referents. This was reflected by congruence patterns in inflectional morphology. It should be noted that the edibility distinction was a property of referents rather than lexemes per se. For example, in the sentence *kłamaγ dzupʰutane I gather a berry, morphemes which mark edibility are used (i.e. *-γ and *-ta-), implying that the berry is ripe. However, using the same lexemes but substituting morphemes marking inedibility, the sentence *kłama dzupʰucane implies that the berry is unripe.

The category of "noun" in Proto-Western is somewhat misleading, as pronouns, determiners and nouns (qua nouns) all inflected in the same way. As such, the term "nominal" has been preferred.

Case and number

Proto-Western nominals inflected for three numbers (singular, dual and plural) and three cases (ergative, absolutive and construct). We shall deal first with number marking.

The singular was unmarked. The dual was marked by the morpheme *-ł- while the plural was marked by the morpheme *-kʷ-. Similarly to English, non-count nouns in Proto-Western took singular inflection.

The absolutive case of inedible nominals was unmarked, while the absolutive of edible nominals was marked by the morpheme *-γ in the singular. The ergative case was marked by the morpheme *-i and the construct case was marked by the morpheme *-u.

Combining the markers for case and number, we arrive at the following table of inflectional suffixes:

| singular | dual | plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| absolutive | inedible | -0 | -ł | -k |

| edible | -γ | |||

| ergative | -ʔi | -łi | -kʷi | |

| construct | -ʔu | -łu | -kʷu | |

The absolutive case was used for the subject of syntactically intransitive verbs and the object of syntactically transitive verbs. The ergative case was used for the subject of syntactically transitive verbs. The construct case was used for those nouns in an NP which were not the head- thus the object of postpositions, possessors, nouns in apposition etc.

- Kʷelaʔi

- kʷela-ʔi

- child-ERG

- yatʰapaʔu

- yatʰapa-ʔu

- garden-CONS

- sãk

- sãk

- in

- ʔašẽ

- ʔašẽ-Ø

- woman-ABS

- daγadzakawa.

- daγadza-ka-wa

- call-3.ERG-3.ABS

Possession

Proto-Western grammaticalised the semantic difference between alienable and inalienable possession. In both cases, the possessive noun phrase was made up by the possessor in the construct case, preceding the possessed nominal. However, inalienably possessed nominals also took a possessive prefix, marking person:

| singular | dual | plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | na- | ʔĩła | ʔĩkʷa- |

| 2nd | če- | tłe- | ʔiʔkʷe- |

| 3rd | ʔe- | łe- | kʷe- |

Those nominals considered to be inalienably possessed were those referring to body parts (including "metaphysical" body parts, such as one's soul), characteristics and family members, which included blood kin and one's spouse but excluding other relations by marriage. Inalienably possessed nouns were considered to be inherent possessions, and as such could not occur without a possessive prefix. Interestingly, the alienable/inalienable distinction also served to change the meaning of nouns. For example, *ʔašẽ woman, when used with a possessive prefix meant "wife", while *łãγa spirit meant "spirit guide" without a possessive prefix and "soul" with one.

- Pʰudaʔu

- pʰuda-ʔu

- chief.CONS

- ʔetʰunyaʔãʔi

- ʔe-tʰunyaʔã-ʔi

- 3SG-brother-ERG

- naʔu

- na-ʔu

- I-CONS

- besadzũ

- besadzũ-Ø

- knife-ABS

- laʔpakaγũ.

- laʔpa-ka-γũ

- steal-3.ERG-3.ABS

Derivation

Proto-Western had a wealth of prefixional derivational morphology, which could mark the speaker's attitude towards the referent, various innate or temporary characteristics of the referent, the location or alignment of the referent and so on. This was a large, open-ended class, and the list of prefixes is too large to be given in full here. As such, it has been relegated to the lexicon.

- Dzamawapʰak

- dzama=wapʰa-k

- red=bean-ABS.PL

- pʰalałki

- pʰala-łki

- grow-3.ABS

- γʷekucu

- γʷekucu

- quickly

- duγakʰeyaʔu

- duγa=kʰeya-ʔu

- good=soil-CONS

- sãk.

- sãk

- in

In addition there was a closed class of derivational morphemes, which changed the meaning of a root, rather than modifying or clarifying it. These suffixes will also be covered in the lexicon.

Classifiers

Proto-Western had a set of morphemes which can probably best be described as "classifiers" or "classifying clitics", although they do rather defy pigeonholing. These were the maids-of-all-work of Proto-Western morphosyntax, as they could function as verbal argument markers, "phoric" pronouns, obligatory classifiers on determiners, bases for pronouns and so on. The details of their usage will be covered as they occur, this section only lists them.

There were nine in total and are listed below, along with some typical referents:

| -wa- | humans, other beings capable of speech: people, gods, spirits, demons, ancestors, animals in fables etc. |

| -ca- | solid, inedible objects: rocks, stones, unripe fruit, babies, non-food animals etc. |

| -ta- | solid, edible objects: most foodstuffs, ripe fruit, meat etc. |

| -ye- | liquids, fire or wind which is tangible: milk, water, flames, breath, urine etc. |

| -γũ- | solid, sticklike objects: sticks, weapons, fingers, penises, legs, arms etc. |

| -łki- | granular masses: grains, berries, soil, sand etc. |

| -kʰiw- | mushy, inedible objects: faeces, mud, rotting things, quicksand etc |

| -če- | mushy, edible objects: pap, mashed foods, pulp of fruit, brains etc. |

| -ši- | intangible things, things which cannot be held: air, celestial bodies, ideas, colours, rivers, trees etc. |

Pronouns

Pronouns are those nominals which substitute other NPs. Proto-Western distinguished two types- personal pronouns and the so-called "phoric" pronouns.

Personal pronouns

The personal pronouns are nominals which refer explicitly to speech-act participants, either the speaker (first person) or the interlocutor (second person). Like other nominals, they distinguish case and number. However, unlike other nominals the first person plural pronoun is formed by suppletion rather than regular nominal inflection.

| absolutive | ergative | construct | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | na | naʔi | naʔu |

| 2sg | ta | taʔi | taʔu |

| 1du | nał | nałi | nału |

| 2du | tał | tałi | tału |

| 1pl | sa | saʔi | saʔu |

| 2pl | tak | takʷi | takʷu |

- Saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- we-ERG

- tak

- ta-k

- you-PL.ABS

- bẽdzanẽtʰã.

- bẽdza-nẽ-tʰã

- know-1PL.ERG-2PL.ABS

- Tałi

- ta-łi

- you-DU.ERG

- na

- na-Ø

- I-ABS

- sabayačʰẽna.

- sabaya-čʰẽ-na

- fight-2PL.ERG-1SG.ABS

"Phoric" pronouns

The "phoric" pronouns differ from the personal pronouns in that their referents are not "fixed", but can be coreferential with any other referent in the discourse world. That is to say, in the discourse world "I" am always "I" and "you" are always "you", but the referent of "it" can vary depending on what we're talking about.

Proto-Western distinguished two types of phoric pronoun: those whose co-referents have already been stated or are already clear by context (anaphora), and those whose co-referents have not yet been stated (cataphora). The latter are particularly common in subclauses. Both pronouns can be coreferential with any other nominal, including personal pronouns.

The anaphoric pronoun was formed by suffixing an appropriate classifier to the stem *ya-, while the cataphoric pronoun was formed by suffixing an appropriate classifier to the stem *kʷi-.

- Saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- we-ERG

- taʔu

- ta-ʔu

- you-CONS

- četʰunã

- če-tʰunã-Ø

- 2SG-father-ABS

- kʰakʷʰadzanẽca.

- kʰakʷʰadza-nẽ-ca

- mock-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

- Kʷiwaʔi

- kʷi-wa-ʔi

- CAT-{human}-ERG

- pʰałki

- pʰa-łki

- everyone-ABS

- tʰũdukałki

- tʰũdu-ka-łki

- fuck-3.ERG-3.ABS

- yawaʔu

- ya-wa-ʔu

- ANA-{human}-CONS

- ʔeʔašẽʔi

- ʔe-ʔašẽ-ʔi

- 3SG-wife-ERG

- kʰakʷʰadzakawa

- kʰakʷʰadza-ka-wa

- mock-3.ERG-3.ABS

- caca:

- caca

- moreover

- yawa

- ya-wa-Ø

- ANA-{human}-ABS

- kʰakʷʰadzawa

- kʰakʷʰadza-wa

- mock-3.ABS

- ye

- ye

- NEG

- γʷey?

- γʷey

- Q

Determiners

The class of determiners in Proto-Western includes demonstratives and quantifiers. Both obligatorily use the classifiers as suffixes, the classifier agreeing with the referent which is being determined.

Additionally, Proto-Western determiners partook of the nature of phoric pronouns, in that in addition to determining another nominal, they can also stand alone with anaphoric/cataphoric reference.

- Pʰacaʔu

- pʰa-ca-ʔu

- every-{solid inedible}-CONS

- kʷela

- kʷela-Ø

- child-ABS

- kʰesałpaca

- kʰesałpa-ca

- defecate-3.ABS

- pʰašiʔu

- pʰa-ši-ʔu

- every-{intangible}-CONS

- maʔu

- ma-ʔu

- place-CONS

- sãk.

- sãk

- in

- Pʰawaʔi

- pʰa-wa-ʔi

- every-{human}-ERG

- kʷe

- kʷe

- but

- yaca

- ya-ca-Ø

- ANA-{solid inedible}-ABS

- čiyekaca.

- čiye-ka-ca

- want-3.ERG-3.ABS

Demonstratives

Proto-Western exhibited a four-way deixis in demonstratives, with different stems to indicate "near me", "near you", "distant from either but still visible" and "distant from either and not visible":

| dže- | near me |

| da- | near you |

| čʰe- | distant from both, visible |

| tʰa- | distant from both, not visible |

Numerals and quantifiers

The Proto-Westerners used a base-eight (octal) numeral system, derived from counting the spaces between fingers rather than the fingers themselves. The basic numerals are:

| cardinal | ordinal | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | takʷa- | takʷadu |

| 2 | ši- | šidu |

| 3 | nałtu- | nałtudu |

| 4 | mẽca- | mẽcadu |

| 5 | ʔudza- | ʔudzadu |

| 6 | mẽči- | mẽčidu |

| 7 | nalši- | nalšidu |

| 10 | ñaγʷa- | ñaγʷadu |

Note that ordinal numerals did not take classifiers, while classifiers were obligatory for cardinal numerals. Multiples of ten are formed by means of the ordinal numeral followed by the cardinal: nałtudu ñaγʷataʔu cubak thirty (lit. third ten) fruits (lit third ten). Other numerals are formed by a coordinated phrase: ñaγʷa ʔudzawa ca lak fifteen (lit. ten and five) men.

Other quantifiers, such as γipa- some, lãca- many etc. also obligatorily take classifiers.

- Lãcawaʔu

- lãca-wa-ʔu

- many-{human}-CONS

- lak

- la-k

- man-PL.ABS

- kʷułuk

- kʷułu-k

- wolf-PL.ABS

- ye,

- ye

- NEG

- natʰẽʔpi!

- na-tʰẽʔpi

- 1SG-daughter

The verb

The Proto-Western verb was inflected for participant reference and evidentiality. It did not mark tense, aspect or mood.

Evidentiality

Verbs inflected for a remarkably detailed system of of evidentiality markers which denoted the origin of the speaker's evidence for a statement. There were eight categories of evidentiality, marked by suffixes occurring directly following the verb's root.

The first set of evidentiality markers indicated that the evidence was gained directly by the speaker via their senses. There were three such markers: *-ya-, which denotes that the speaker witnessed the action visually; *-pũ-, which denotes that the speaker tasted or smelled the evidence and *-dži-, which denotes that the speaker felt or heard the evidence.

- Błamapũtʰa.

- błama-pũ-tʰa

- fart-EVID-2.ABS

The second set of markers indicated that the evidence is secondhand and not directly derived from the speaker's experience. There were two such markers: *-bã-, which indicates that the information was received via hearsay and may or may not be accurate and *-lši-, which indicates that the speaker has no doubts about the information he has received.

- La

- la-Ø

- man-ABS

- wadžedzabãkawa.

- wadžedza-bã-ka-wa

- kill-EVID-3.ERG-3.ABS

The third set indicated that the information was not personally experienced but was inferred from indirect evidence. There were three of these markers: *-luʔki-, which indicated that there was physical evidence; *-ʔu-, which indicates that the information is general knowledge and *-kʷe-, which indicates that the information is inferred or assumed based on the speaker's past experience of similar situations.

- Yama

- yama-Ø

- sun-ABS

- mašeʔuʔi.

- maše-ʔu-ʔi

- shine-EVID-3.ABS

Evidentiality markers do not seem to have been obligatory for each verb, although it seems that they were particularly common when new information or situations were presented.

Participant reference

Unlike evidentiality marking, which was optional, marking the core participants of a speech act (agent, patient or experiencer) is obligatory on verbs. Verbs exhibit concord markers for both ergative and absolutive participants in the speech act (transitive verbs taking both while intransitive verbs only take the latter).

Participants were marked by means of suffixes, with absolutive markers following ergative markers. Separate third person absolutive markers are absent, instead classifiers were used. Note also that number marking is defective: the dual number is not marked (congruence with dual-number participants is effected by means of singular inflexions) and number is not distinguished at all in the third person.

| ergative | absolutive | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| singular/dual | plural | singular/dual | plural | |

| 1st person | -ne | -nẽ | -na | -nã |

| 2nd person | -čʰe | -čʰẽ | -tʰa | -tʰã |

| 3rd person | -ka | -ka | ||

Participant markers were anaphoric: they could stand as the only reference to an argument in the clause (i.e. Proto-Western was pro-drop). Note that in ditransitive verbs, only the theme (direct object) was marked on the verb- the recipient was not.

- Γʷiwadzanetʰa.

- γʷiwadza-ne-tʰa

- give_birth-1.ERG-2.ABS

Syntax

We can reconstruct the syntax of Proto-Western with relative assurance. The daughter languages exhibit clear remnants of the protolanguage's OV typology, even where the fundamental word order has changed to VO. By extrapolation of features associated with OV languages, we can arrive at a fairly confident reconstruction of Proto-Western syntax, which is happily confirmed by our earliest texts in the first attested descendant languages.

It appears that Proto-Western was a fairly rigid left-branching language, with all that implies- postpositions, OV sentence structure and modifiers preceding their heads.

Phrase structure rules

Noun phrases

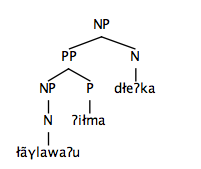

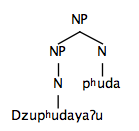

| NP → (S, PP, NP) N |

The noun phrase is made up of a nominal preceded by zero or more modifiers. Permissible modifiers are other noun phrases, postpositional phrases or relative clauses. When an NP acts as the modifier in another NP, the head of the modifying NP will be found in the construct case.

- łãγlawaʔu

- łãγlawa-ʔu

- priest-CONS

- ʔiłma

- ʔiłma

- without

- dłeʔka

- dłeʔka-Ø

- tribe-ABS

- Dzupʰudayaʔu

- Dzupʰudaya-ʔu

- Dzupʰudaya-CONS

- pʰuda

- pʰuda-Ø

- chief-ABS

Postpositional phrases

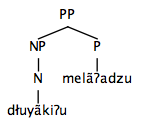

| PP → NP P |

A postpositional phrase is made up of a postposition preceded by a noun phrase, the head of which is found in the construct case. Only NPs can be the complement of a postposition.

- dłuyãkiʔu

- dłu=yãki-ʔu

- long=river-CONS

- melãʔadzu

- melã-ʔadzu

- along-away

Verb phrases

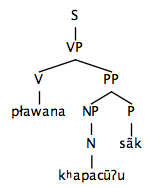

| VP → (Complement) V (Adjunct) |

A verb phrase is minimally composed of an inflected verb. This can be followed by an optional Adjunct, which may be a postpositional phrase, an adverb, an adverbial clause or a sentential particle.

Additionally, a VP may include a Complement made up of one or two NPs, which precedes the verb. Syntactically monotransitive verbs obligatorily have a single NP as their complement, ditransitive verbs will have two NPs and intransitive verbs will not have a complement. Note that the direct object (theme) of a ditransitive verb will occur closest to the verb.

- Pławana

- pława-na

- walk-1SG.ABS

- kʰapacũʔu

- kʰapacũ-ʔu

- forest-CONS

- sãk.

- sãk

- in

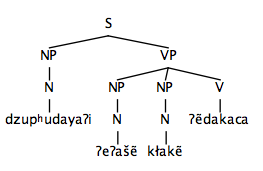

- Dzupʰudayaʔi

- dzupʰudaya-ʔi

- hunter-ERG

- ʔeʔašẽ

- ʔe-ʔašẽ-Ø

- 3SG-wife-ABS

- kłakẽ

- kłakẽ-Ø

- skin-ABS

- ʔẽdakaca.

- ʔẽda-ka-ca

- give-3.ERG-3.ABS

Clauses

| S → (NP) VP |

A clause (sentence)- either an embedded or a matrix clause- is minimally composed of a VP. Should the head of the VP be mono- or ditransitive, the VP may be preceded by an NP, the head of which must be in the ergative case.

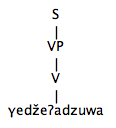

- Γedžeʔadzuwa.

- γedže-ʔadzu-wa

- run-away-3.ABS

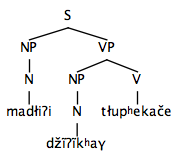

- Madłiʔi

- madłi-ʔi

- bear-ERG

- džĩʔĩkʰaγ

- džĩʔĩkʰa-γ

- honey-ABS

- tłupʰekače.

- tłupʰe-ka-če

- find-3.ERG-3.ABS

Complex clauses

Complement clauses

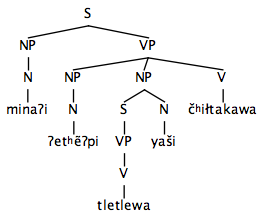

A complement clause is one which functions as an argument of another clause (the matrix clause). As such, in Proto-Western, complement clauses were treated as a subtype of NP, in which the head was an anaphoric pronoun (which generally took the intangible classifier) modified by a preceding clause. The main verb of the matrix clause was prototypically a verb of cognition or volition (want, believe, think).

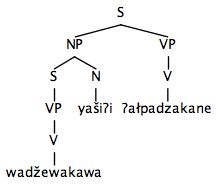

- Wadžewakawa

- wadžewa-ka-wa

- kill-3.ERG-3.ABS

- yašiʔi

- ya-ši-ʔi

- ANA-{intangible}-ERG

- ʔałpadzakane.

- ʔałpadza-ka-ne

- anger-3.ERG-1SG.ABS

- Minaʔi

- mina-ʔi

- mother-ERG

- ʔetʰẽʔpi

- ʔe-tʰẽʔpi-Ø

- 3SG-daughter-ABS

- tletlewa

- tletle-wa

- prepare_leather-3.ABS

- yaši

- ya-ši-Ø

- ANA-{intangible}-ABS

- čʰiłtakawa.

- čʰiłta-ka-wa

- teach-3.ERG-3.ABS

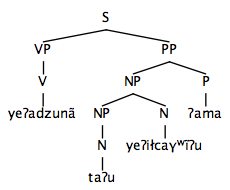

Adverbial clauses

| This is unforgivably terse. Forgive me. |

An adverbial clause is one which serves an adverbial function. Rather than a core argument of a main clause (without which a clause would not be complete), adverbial clauses are adjuncts to a main clause, adding further information.

Primarily, adverbial clauses were subtypes of postpositional phrases, the complement of which was obligatorily an NP. As an adverbial clause could often have verbal meaning (e.g. "we will go when you arrive"), the verb is normally expressed via a PP, with the verb undergoing nominalisation and governing a subordinate NP.

- Yeʔadzunã

- yeʔadzu-nã

- leave-1PL.ABS

- taʔu

- ta-ʔu

- 2SG-CONS

- yeʔiłcaγʷĩʔu

- yeʔiłca-γʷĩ-ʔu

- come-VN-CONS

- ʔama.

- ʔama

- with

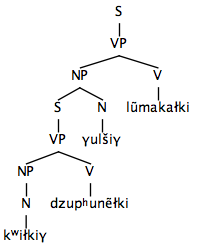

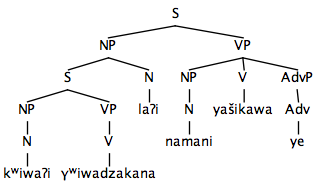

Relative clauses

Relative clauses are those clauses which function simply as nominal modifier. In relative clauses, the relativised NP (which is coreferential with the nominal which is modified by the clause) is represented by a cataphoric pronoun.

- Kʷiłkiγ

- kʷi-łki-γ

- CATA-{granular}-ABS

- dzupʰunẽłki

- dzupʰu-nẽ-łki

- gather-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

- γulšiγ

- γulši-γ

- millet-ABS

- lũmakałki.

- lũma-ka-łki

- grind-3.ERG-3.ABS

- Kʷiwaʔi

- kʷi-wa-ʔi

- CATA-{human}-ERG

- γʷiwadzakana

- γʷiwadza-ka-na

- give_birth-3.ERG-1SG.ABS

- laʔi

- la-ʔi

- man-ERG

- namina

- na-mina-Ø

- 1SG-mother-ABS

- yašikawa

- yaši-ka-wa

- marry-3.ERG-3.ABS

- ye.

- ye

- NEG

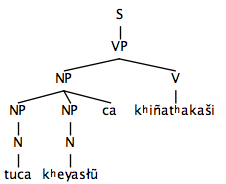

Coordination

Two patterns of coordination can be distinguished in Proto-Western: clausal and phrasal coordination. In phrasal coordination, the coordinator is placed after the head of the final phrase to be coordinated. However, when whole clauses are joined, the coordinator is placed after the head of the first phrase in the clause.

- Tuca

- tuca-Ø

- house-ABS

- kʰeyasłũ

- kʰeyasłũ-Ø

- wall-ABS

- ca

- ca

- and

- kʰiñatʰakaši.

- kʰiñatʰa-ka-ši

- build-3.ERG-3.ABS

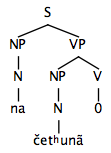

Nominal predicates

Nominal predicates, or copular phrases, can be formed in one of two ways. Where the phrase indicates identity (e.g. John is my brother- in English the second NP in copular phrases of this type are generally definite), Proto-Western made use of a zero-copula, which was unmarked for participants. Note that both NPs in a copular phrase are in the absolutive case:

- Na

- na-Ø

- 1SG-ABS

- četʰunã.

- če-tʰunã-Ø

- 2SG-father-ABS

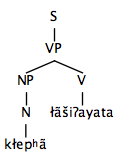

However, where the phrase indicates membership in a larger group (e.g. John is a lawyer), normally the second element is changed into a stative verb by means of the suffix *-ʔaya-, which immediately follows the root:

- Kłepʰã

- kłepʰã-Ø

- animal-ABS

- łãšiʔayata.

- łãši-ʔaya-ta

- horse-be-3.ABS

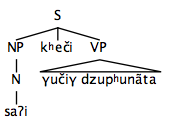

Sentential particles

Proto-Western had a wide range of grammatical particles. These were uninflected morphemes which acted as adjuncts to the main clause, indicating additional information. These can be divided into three main categories: discourse particles, speech act particles and adverbs.

Discourse particles

Discourse particles overlap to a degree with coordinators, their function was to link together clauses and indicate the relationship between them. As such, they occurred after the head of the first phrase of the clause (Wackernagel's position). This was a closed class of particles, including only six: cał also, dlã by contrast, pʰã then/next, duk therefore, kʰeči instead, džet however.

- Saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- 1PL-ERG

- kʰeči

- kʰeči

- instead

- γučiγ

- γuči-γ

- fish-ABS

- dzupʰunãta.

- dzupʰu-nã-ta

- catch-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

Speech-act particles

This was another closed class of particles, and was smaller than that of the discourse particles. Speech-act particles added further information to a clause or phrase, indicating that the speech act was non-declarative, being rather negative (ye) or interrogative (γʷey). When they modified the whole clause, they were placed in the final position in the clause- the last adjunct element of a VP. However, when modifying a phrase, only they preceded the head.

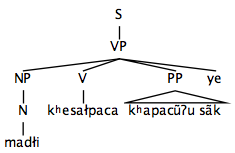

- Madłi

- madłi-Ø

- bear-ABS

- kʰesałpaca

- kʰesałpa-ca

- defecate-3.ABS

- kʰapacũʔu

- kʰapacũ-ʔu

- forest-CONS

- sãk

- sãk

- in

- ye.

- ye

- NEG

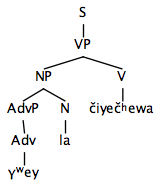

- Γʷey

- γʷey

- which

- la

- la-Ø

- man-ABS

- čiyečʰewa?

- čiye-čʰe-wa

- want-2SG.ERG-3.ABS

Adverbs

Adverbs made up a large open-ended class, including temporal adverbs such as cʰuy yesterday, adverbs indicating the internal structure of the speech act such as tłãtłã repeatedly as well as simple adverbs of manner. Adverbs always occupied the adjunct slot of a VP.

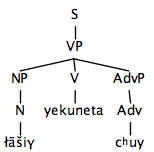

- Łãšiγ

- łãši-γ

- horse-ABS

- yekuneta

- yeku-ne-ta

- eat-1SG.ERG-3.ABS

- cʰuy.

- cʰuy

- yesterday

Transformations

The role transformations played in Proto-Western syntax is not yet fully understood. However, we can reach some conclusions about how transformations were used for pragmatic purposes, emphasising or deemphasising participants in an utterance.

Valence adjusting

Proto-Western lacked morphological passive-type structures (reflexives, passives, medials, antipassives etc). However, it did have a number of strategies for increasing or decreasing the valence of a verb, which had various pragmatic effects.

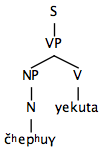

To deemphasise the agent of a transitive verb and consequently emphasise the patient, the agent could be omitted, reducing the verb's valence by one.

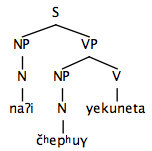

- Naʔi

- na-ʔi

- 1SG-ERG

- čʰepʰuγ

- čʰepʰu-γ

- deer-ABS

- yekuneta.

- yeku-ne-ta

- eat-1SG.ERG-3.ABS

becomes:

- Čʰepʰuγ

- čʰepʰu-γ

- deer-ABS

- yekuta.

- yeku-ta

- eat-ABS

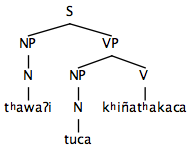

Similarly, to deemphasise the patient and emphasise the agent, the patient could be incorporated within the verb. This reduced the verb's valence by one. The agent of a monotransitive verb so promoted would be cast in the absolutive case:

- Tʰawaʔi

- tʰa-wa-ʔi

- that-{human}-ERG

- tuca

- tuca-Ø

- house-ABS

- kʰiñatʰakaca.

- kʰiñatʰa-ka-ca

- build-3.ERG-3.ABS

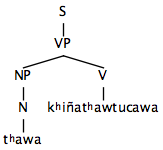

becomes:

- Tʰawa

- tʰa-wa-Ø

- that-{human}-ABS

- kʰiñatʰatucawa.

- kʰiñatʰa-tuca-wa

- build-house-3.ABS

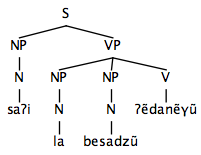

However, in ditransitive verbs, only the theme (the direct object) could be incorporated in the verb. The result is then a monotransitive verb with an incorporated theme:

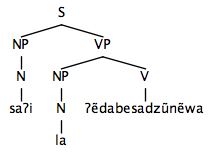

- Saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- 1PL-ERG

- la

- la-Ø

- man-ABS

- besadzũ

- besadzũ-Ø

- knife-ABS

- ʔẽdanẽγũ.

- ʔẽda-nẽ-γũ

- give-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

becomes:

- Saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- 1PL-ERG

- la

- la-Ø

- man-ABS

- ʔẽdabesadzũnẽwa.

- ʔẽda-besadzũ-nẽ-wa

- give-knife-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

Note that the patient of a verb could not be de-emphasised by being omitted. A sentence such as **naʔi yekune **I eat would be ungrammatical.

Topicalisation

| Yeah, that's it. Sorry. |

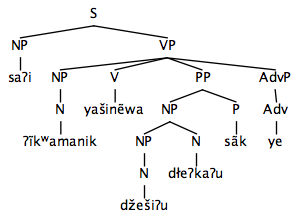

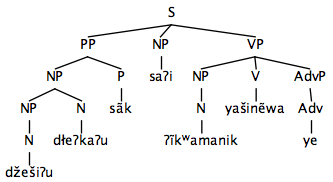

To emphasise adjuncts, they could be left-dislocated to the beginning of the clause:

- Saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- 1PL-ERG

- ʔĩkʷaminak

- ʔĩkʷa-mina-k

- 1PL-mother-ABS.PL

- yašinẽwa

- yaši-nẽ-wa

- marry-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

- džešiʔu

- dže-ši-ʔu

- this-{intangible}-CONS

- dłeʔkaʔu

- dłeʔka-ʔu

- tribe-CONS

- sãk

- sãk

- in

- ye.

- ye

- NEG

becomes:

- Džešiʔu

- dže-ši-ʔu

- this-{intangible}-CONS

- dłeʔkaʔu

- dłeʔka-ʔu

- tribe-CONS

- sãk,

- sãk

- in

- saʔi

- sa-ʔi

- 1PL-ERG

- ʔĩkʷaminak

- ʔĩkʷa-mina-k

- 1PL-mother-ABS.PL

- yašinẽwa

- yaši-nẽ-wa

- marry-1PL.ERG-3.ABS

- ye.

- ye

- NEG

Sample Text

| Read: I'm too lazy. |

Relay convention dictates that at this point a translation of the Sinakan Text is presented. However, translating this text into Proto-Western would probably be a little anachronistic (not to mention that the language lacks words for "king" and "throne"). In addition, the standard "original" has since become the Adata version (or, properly, the English retranslation of the Adata version) with its panoply of modal forms, which would be far too much effort to render suitably into Proto-Western.

So, instead I've come up with a new text, a Schleicher's fable of sorts.

*Łãšiγ mẽγuk ca - The horse and the sheep

Γʷeyeʔu tabe łãšiʔi mẽγuk čeldawata. ʔašẽʔi takʷaduʔu mẽγuʔu tʰula besawakʰiw, kʷelaʔi šiduʔu mẽγuγ γlaʔtawata, laʔi nałtuduʔu mẽγuγ wadžedzakata. Yawaʔu kʰayaʔu nat mẽcaduʔu mẽγuγ kʷekʷuta.

Łãšiʔi mẽγuγ kʷiši dzačiwaši: yamayaʔakʷi duk mẽγuk tʰatʰawata yašiʔi ʔuyadzadzawane.

Takʷataʔu mẽγuʔi łãšiγ kʷišidzačiwaši: γiyawane yašičiyenaši. Kʷitaγ γedžeta γʷekuca łãšiγ pʰapʰaʔtayečita yekuta ca. Yamayaʔakʷi taʔu γʷekutʰatʰawaši yaši bẽdzaluʔkiwaši ye. Wetweʔnãca kʷe bẽdzawaši. Taʔi kʷe cał yamayaʔaʔu γʷełbuγ tʰuyakʷewata!

Čʰešiʔu γiyaγʷĩʔu kʷucu, łãšiγ γedžeta takadłeʔu ke.

A horse on a hill saw some sheep. A woman was cutting away the wool of the first sheep, a child was milking the second sheep, a man was slaughtering a third sheep. On their fire, a third sheep was being cooked.

The horse said this to a sheep: It pains me to see humans using sheep like this.

One sheep said this to the horse: I want you to listen to me. It pains me to see the horse who runs swiftly being shot and eaten. Humans do not know how to use your swiftness. But next year they will know. Then you too will be the slave of the humans!

Having heard this, the horse fled into the plain.

Most of this text is straightforward, but a few things bear mentioning. Evidentiality has only been marked in two places- in bẽdzaluʔkiwaši ye they do not know, the sheep indicates that he knows this due to the physical evidence and in tʰuyakʷewata you will become, the sheep is wryly referring to the past experience of his own species. Note also that wetweʔnãca next year does not neccessarily refer exactly to next year, rather to a far-off point in the future.